Pipes and Pipers

History

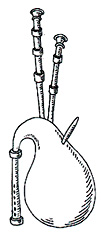

Piob Mhor - The Great Highland Bagpipe

Greg Dawson Allen

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PIOB MHOR

"In its origin the bagpipe was never the property of one people or one nation but was a universal musical instrument. This powerful instrument has a long pedigree and derives from earlier and prehistoric reeded pipes such as "shawms" and "hornpipes", known and played in Near Eastern and Egyptian civilisations from before 2,500 BC." From The Book of the Bagpipe, Hugh Cheape, 1999.

A theory of the ancient world alleges that Japheth, the eldest son of Noah, fathered a son, Gomar and that from his seed all Celtic peoples are descended. To further the claim, it is also believed that Gillidh Callum was the piper to Noah and that he danced to the pipe music over two vine plants crossed, in celebration of the first making of wine from the newly planted vineyard. (MANSON 2)

The Greek poet Aristophanes, around 425 BC, spoke of the pipers from Thebes

as "blowing on a pipe with a dog skin with a chanter of bone." (CHEAPE

3)

The Greek poet Aristophanes, around 425 BC, spoke of the pipers from Thebes

as "blowing on a pipe with a dog skin with a chanter of bone." (CHEAPE

3)

The Angelic Bagpiper, from a carving in Rosslyn Chapel, Midlothian, 1440.

The 'shawms' and 'horn pipes' of Egypt before 2500 BC originating in Asia Minor were known by the Greek name of Aulds. (CHEAPE 4) There is anecdotal evidence that the Roman Emperor Nero played on a 'Flute with a bladder' (MANSON / CANNON 5)

The bag-pipes seemingly having no distinction of the higher classes, let alone in the halls of the court, but commonly referred to as being an instrument of the street musician. (CHEAPE 6)

Nero, on the eve of the destruction of Rome, pleaded to the Gods that if they would exercise their gifts and turn the tide of fate he would play the bag-pipes in public for all to see. The Archbishop of Novogorad was described by the Czar of Russia in 1569 as 'Fitter for a bag-piper leading dancing bears than for a Prelate.' (MANSON 7)

Pipers in Greece used circular breathing, in the same way that Australian Aborigines do when playing the didgeridoo, keeping air in the inflated cheeks whilst inhaling through the nose, thereby maintaining a continuous cycle of breath. A cheek strap relieved the stress on the facial muscles avoiding the unfortunate 'Disfigurement of Athene'. (CANNON 8)

In the 1st century AD Roman Catholic tradition states that the shepherds who witnessed the baby Jesus in Bethlehem celebrated his birth by playing on bag-pipes. In furthering this story both the German artist Albrecht Durer in the 16th century and an unaccredited Dutch illuminator both, amongst others, represented the nativity; the former by a shepherd playing on a set of bag-pipes, and by the latter depicting an angel clearly playing on a pipe and bag.

Each country had its own specific designs for the pipe and bag. Some did not use drone pipes, others used drones which varried in number from one to four. In some cases a double chanter was employed. Animal skin pipe bags also came in a variety of shapes and sizes.

As pipes developed in each region in design and construction so the air

bag was carefully chosen, and not, as it may seem, adapted from a random

carcass. The shape of the bladder, as were most bags fashioned from before

an effectual method of stitching could be employed, needed to replicate

an easy flow of air as near to human breathing could allow. Goat or kid's

bladders were widely used as were dogs and to a lesser extent, calf.

As pipes developed in each region in design and construction so the air

bag was carefully chosen, and not, as it may seem, adapted from a random

carcass. The shape of the bladder, as were most bags fashioned from before

an effectual method of stitching could be employed, needed to replicate

an easy flow of air as near to human breathing could allow. Goat or kid's

bladders were widely used as were dogs and to a lesser extent, calf.

Calf and sheep bladders have a worthy place in history and were still

in use by the 19th century, usually hanging beneath a woman's long skirt

as a mode of transportation for the usigue-bathe or whiskey safely hidden

from the gaze of the excise men. A drop of the water of life is synonymous

with the piper and in those days of the illicit stills and the making of

music the bladder served two valuable purposes.

The Sackpfeiff, a 16th century German bagpipe.

Names given to the bag-pipes were localised. European bag-pipes in the 17th century were known as, Bignou in Lower Brittany, Cornamusa in Italy, in Rome Tibia Utricularis and as Sackpfeiff in Germany. Other names appeared such as Tiva, Ciarmella, Samponia and Zampugna. (MANSON 9)

Whilst the bag-pipe retained a basic configuration, the number of notes, mechanisms and drones etc varied from country to country. For example, a selection of bag-pipes played on the continent in the 17th century;

1) The Cornemuse had an eight aperture chanter but without drones, inflated only by the mouth.

2) The Chalemise (Shepherd's Pipe) also inflated by the mouth, had two drones and a chanter with ten holes.

3) The Mussette was fed by air from a bellows, played with a chanter of twelve notes. It also possessed other apertures with valves controlled by mechanical keys with four reeds for drones, all enclosed inside a barrel. The construction and ornamentation of the mussette removed the bag-pipe from the sole use of the itinerant street player into the Royal court with distinguished patrons. Players of the Mussette wore the title of 'Royal Piper'.

4) The Surdelina of Naples - a bag-pipe consisting of a pair of drones matched with a pair of chanters. It also had an unspecified amount, but numerous keys.

5) The common bag-pipe of the Italian peasant with two chanters each with a single key and paired to one single drone. (MANSON 10)

Although continental Europe enjoyed the tones of the bag-pipe it was not

until the 12th century that the English first included the instrument in

any of their historical records. It was to be into the following century

before Scotland could make any claim to the bag-pipe.

Although continental Europe enjoyed the tones of the bag-pipe it was not

until the 12th century that the English first included the instrument in

any of their historical records. It was to be into the following century

before Scotland could make any claim to the bag-pipe.

Documents, mostly accountancy books noting payment to musicians for work done, tend to list the pipe as 'the drone', 'the flute' or simply 'the pipes', making no distinction to the bag-pipe as it was and therefore it may have been introduced even earlier than supposed. Alexander III of Scotland employed musicians, as did David II, when in 1362 a payment of 40 shillings was made to the pipes. During James III's reign (1452-1488) English pipers were paid, ' 8 pounds 8 shillings for playing at the castle.' (CHEAPE 11)

An inventory of Henry VIII's musical collection made after his death in 1547 lists five sets of pipes including, 'A baggepipe with pipes of ivorie, the bagge covered with purple vellat.' (CHEAPE 12)

An early 17th century German bagpipe with ornate single bass drone and hornpipe chanter.

Whatever the style, country of origin, or number of drones, the defining part of any set of pipes is the melody carrying pie - the "chanter". There are two basic types: The cylindrical chanter is as straight and simetrical as the raw material - wood or bone - will allow. An extension of horn is often added to the end. The reed is of a simple, single piece of cane with a vibrating tongue cut in it. (CANNON 14)

The conical chanter is turned on a wood-lathe to create the 'trumpet flare'. The bore is an expertly crafted narrow cone, tapering wider from top to bottom. A double reed is usually fitted. This is the chanter used in the Great Highland Bagpipe.

As would be expected the sounds separate the two styles - the conical giving a high shrill and nasal sound, whilst the cylindrical chanter gives a softer sound. The former is the distinctive sound of the Great Pipe, the latter the quieter Northumbrian or small pipes.

The discovery of the stock and horn so excited Robert Burns during his collaboration with George Thomson in their collection entitled 'Select Scottish Airs', that he wrote to his colleague on the subject (CHEAPE 15)

"I have at last gotten one, but it is a very rude instrument. It is composed of three parts: the stock, which is the hinder thigh bone of a sheep, . . . the horn, which is a highland cow's horn, . . . and lastly an oaten reed exactly cut and notched like that which you see every shepherd-boy have, when the corn-stems are green and full-grown. . . The stock has six or seven ventiges in the upper side and one back ventige, like the common flute. This one of mine was made by a man from the Braes of Athole, and is exactly what the shepherds were wont to use in that country." Robert Burns, from a letter to George Thomson dated 19th November, 1794.

From the distinctive sound to the distinctive look of the Great Pipe - the Piob Mhor.

From an airtight bag, five hollow pipes branch out - four fitted with reeds whilst the fifth is a mouthpiece into which air from the piper's lungs is blown, filling the bag as a reserve supply. The three drones are each fitted with a reed of split cane set at the base of the drone, ensuring that the air from the bag vibrates the 'tongue' of the reed into motion.

A single note is attributable to each drone which is tuned by a 'slider'. The tuning of the Piob Mhor is a necessary evil even to the trained ear. A few moments of tuning can be a source of annoyance - the reeds have to allow for the change of the cool air from the bag inflated by the piper's breath, to the warm breath which follows, inevitably working as opposites on the sensitive reeds.

The blowpipe has a valve which prevents air from returning up the pipe, constituting a one-way flow to the bag. The large bass drone (Aon Chrann mor) which is rested, usually on the left shoulder of the piper, has two 'sliders', the other two tenor drones (Na Dha bheaga) having only one.

The skill of playing has to be blended with the art of posture and stance. The piper's left arm should only squeeze the bag with enough pressure to feed the drones with air to sound the notes without disturbance or distortion. The bag is held towards the front of the piper's body allowing the shorter drone to rest on the shoulder.

Modern pipes, in the early 20th century were made of tropical hard woods, usually black ebony and black wood from Africa or cocas wood from the Caribbean with decorative rings or ferrules made of ivory. Sometimes silver was used for the lower ferrules. Prior to and throughout the 18th century, local hard woods were used, commonly holly and laburnum, again horn and bone being added for decoration.

Pipers, particularly teachers, were adept craftsmen in both creators of music and their instruments. Many used to make their own pipes. A notable Scottish piper, John Ban MacKenzie, who died in 1864, thought to be the last of these makers was siad to have killed the sheep, stitched the bag, turned the drones, chanter and blow-pipe on his simple foot-peddled lathe, cut the oaten reeds, composed the tunes and played them, all with his own hands. (DONALDSON 18)

The inside of the drones of the best manufactured pipes were lined with metal where there is cause for friction in the tuning slides.

This then is the Piob Mhor - the Great Highland Bagpipe, the musical instrument that has been associated with Scotland, in both war and peace, for centuries past.

History of The Great Pipes

From "The Pipers' Assistant" edited by John McLachlin (piper

to Neill Malcolm Esq.) and published in 1854 by piper and bagpipe-maker

Alexander Glen, Edinburgh.

If the simplicity of a musical instrument be the greatest criterion of its antiquity, the GREAT HIGHLAND BAGPIPE must be allowed to be of a very early invention. It is founded on the oaten pipe of primitive times. The chanter made of wood, the most sonorous of all substances, seems to have been the first step towards the improvement of the instrument. The bag and drones were at some subsequent period added; and in that improved state it has been handed down to us by a very remote generation, as is evident by the impressions we see on old coins. "There is now in Rome a most beautiful bas relievo, a Grecian sculpture of the highest antiquity, of a Bagpiper playing on his instrument, exactly like a modern Highlander. The Romans, in all probability, borrowed it from the Greeks, and introduced it among their swains; and the modern inhabitants of Italy still use it, under names of Piva and Cornumua.

"That master of music, Nero, used one; and had not the empire been so suddenly deprived of that great artist, he would (as he graciously declared his intention) have treated the people with a concert, and among other curious instruments, would have introduced the Utrcularius or Bagpipe. NERO perished; but the figure of the instrument is preserved on one of his coins.

"The Bagpipe, in an unimproved state, is also represented in an ancient sculpture, and appears to have had two long pipes or drones, and a single short pipe for the fingers."

Some think that it has been introduced into Scotland by the Romans; but the most probable conjecture is, that the Gauls, when they poured their tribes over the North, brought it into that kingdom; and that the Gaelic, and the "Garb of old Gaul," or Highland dress, were neutralized here at the same time.

MR PENNANT, by means of an antique found at Richborough in Kent, has determined that the Bagpipe was introduced at a very early period to Britan; whence it is probable, that both the Irish and the Danes might borrow the instrument from the Caledonians, with whom they had such frequent intercourse.

ARISTRIDES QUINTILANUS informs us, that it prevailed in the Highlands in very early ages, but is silent as to its having been brought in at the Roman Invasion. Indeed, people seldom choose to adopt the music, dress and language, of their conquerors. OSSIAN makes no mention of it in his beautiful Poems. The harp was the favourite instrument of his days.

So much for its antiquity. Now for its utility - The Attachment of the Highlanders to their music is almost incredible, and on some occasions it is said to have produced effects little less marvellous than those ascribed to the ancient music.

"Its martial sounds can fainting troops inspire

With strength unwonted and enthusiasm raise."

At the battle of Quebec, in 1760, while the British troops were retreating in great disorder, the General complained to a Field Officer in FRASER'S Regiment, of the bad behaviour of his corps. "Sir," said the Officer, with some warmth, "you did very wrong in forbidding the Piper's to play this morning; nothing encourages the Highlanders so much in the day of battle; and even now they would be of some use." "Let them blow like the devil, then," replied the General, "if it will bring back the men." The Pipers were then ordered to play a favourite martial air; and the Highlanders, the moment they heard the music, returned and formed with alacrity in the rear.

In the late war in India, Sir EYRE COOTE made the Highland Regiments a present of fifty pounds to buy a set of Bagpipes, in consideration of their gallant conduct in battle of Porto Nuovo, where the British troops had to cope with double their number. When the line was giving way, a Piper in Lord MACLEOD'S Regiment struck up Cogdah na sith, i.e., War or Peace; which so invigorated the Highlanders that they suddenly fell upon the ranks of the enemy and restored the fortunes of the day.

In 1745, when the Duke of Cumberland was leaving Nairn to meet the adherents of Prince Charles at Culloden, the clans Munro, Campbell, and Sutherland accompanied him-observing he Pipers carrying their Pipes preparatory to their march, he enquired of one of his officers, "What are these men going to do with such bundles of sticks, I can supply them with better implements of war? - The officer replied , "Your Royal Highness cannot do so, these are bagpipes,- the Highlanders music in peace and war-Wanting these all other implements are of no avail, and the Highlanders need not advance another step, for they will be of no service!"

When the brave 92d Highlanders took the French by surprise in the late Peninsular war, the Pipers very appropriately struck up "Hey Johnny Cope, are ye wauking yet;" which completely intimidated the enemy, and inspired our gallant heroes with fresh courage to the charge, which as usual was crowned with victory. Innumerable anecdotes of a similar nature might be produced, to prove the great utility of this ancient and warlike field instrument, and the expediency of its being used by all Highland Regiments; but the limits of a short Preface will not admit of it.

In times of peace the sound of the Pipe is heard in the halls of our Chieftains. The gatherings regale their ears while the feast is spread on their hospitable boards, and the merry measure of the reel invites them to the floor.

Than the sound of Bagpipe no other music is more grateful the Highland ear,and to the Scottish Dancer in general. - For him it is an influence, and bestows a vigour and enthusiasm which place all other instruments in the shade: And here let us pay a tribute of respect to one who, although perhaps the most exquisite violinist in Scotland, as a player of Highland Reels, and Strathspeys, exceeds in his attachment to the Highland Bagpipe - we allude to W****** B******, Esq, of Endinburgh: this gentleman at the venerable age of eighty-three, when in his walks he hears the sound of the Pipe, will hasten to the spot, and, after giving the itinerant Piper, or street player a handsome reward for this special performance, will withdraw to a passage or common stair to have what he styles "a wee bit dance to himsel."

On occasions of ceremony, as, for instance, on a visit to a neighbour, the chief of a Highland clan was attended by a retinue, called his tail. The tail was composed of the henchman; the bard or poet; the bladier or spokesman; the gillemore or bearer of the broadsword; the gillecasflue, whose business it was to carry the chief over fords; the gulleconstraine, who led the chief in dangerous passes; the gulletruishanarnish, or carrier of the baggage; the piper; and lastly the piper's gilley, who, as his master was always a gentleman, carried the pipes. But a writer on the Highlands, thus speaks on the piper's functions:- "In a morning when the chief is dressing, he walks backwards and forwards, close under the window, without doors, playing on his bagpipe, with a most upright attitude and majestic stride. It is a proverb in Scotland, namely, the stately step of a piper. When required, he plays at meals, and in an evening is to divert the guests with the music when the chief has company with him; his attendance in a journey, or at a visit.

His gilley holds the pipe till he begins; and the moment he has done with the instrument, he disdainfully throws if down upon the ground, as being the only passive means of conveying his skill to the ear, and not a proper weight for him to carry or bear at other times. But, for a contrary reason his gilley snatches it up; which is, that the pipe may not suffer indignity from its neglect."

CLANS - TRAITS OF MANNERS

In the Lowlands of Scotland the feudal system was firmly establised, and

till this day all holdings of heritable property are feudal. There was

a time when the feudal and patriachal may be said to have blended, and

it is difficult now to say how the one ended and the other began. The patriarchal

or clan system existed longest in the Border districts, Galloway, and the

Highlands. Each of these had its own chief, and was a torment to the sovereign.

A Scotsman of the present day can tell the names by which the clans of

these districts were respectively distinguished. On the Borders there were

Kers, Scots, Elliots, Armstrongs, Johnstones, Jardines, Grahams, &c.

In Galloway (shires of Wigton and Kircudbright,) the clans were Celtic,

and there were found McCullochs, M'Clumphas, M'Taggarts, M'Kellars, M'Lellans, &c.

In the Highlands and Islands there were latterly about forty distinct clans

with several remnants of tribes, called broken tribes. Each clan possessed

three distinguishing tokens independently of its surname; these were its

badge, its slogan or war-cry and its tartan. The following are the names

of the principal Highland clans with their badges:

Buchanan, birch; Cameron, oak; Campbell, myrtle; Chisholm, alder; Colquhoun,

hazel; Cumming, common sallow; Drummond, holly; Farquharson, purple foxglove;

Ferguson, poplar; Forbes, broom; Fraser, yew; (some families the strawberry);

Gordon, ivy; Graham, Laurel; Grant, cranberry heath; Gun, rosewort; Lamont,

crabapple; M'Allister, five leaved heath; M'Donald, bell heath; M'Donnell,

Mountain heath; M'Dougall, cypress; M'Farlane, cloud berry bush; M'Gregor,

pine; M'Intosh, boxwood; M'Kay, bullrush; M'Kenzie, deer grass; M'Kinnon,

St John's wort; M'Lachlan, mountain ash; M'Lean, Blackberry heath; M'Leod,

red wortle-berries; M'Nab, rose blackberries; M'Neil sea ware; M'Pherson,

variegated boxwood; M'Rae, fir-club-moss; Monro, Eagle's feathers; Menzies,

ash; Murray, Juniper; Ogilvie, hawthorn; Oliphant, the great maple; Robertson,

fern; Rose, brier rose; Ross, bear berries; Sinclair, clover; Stewart,

thistle; Sutherland, cat's-tail grass. Sprigs of these badges were worn

in the bonnet; but the chief of each clan was entitled to wear two eagle's

feathers in addition.

Such is a pretty accurate list of the clans; some, however, are evidently Lowland; and it is difficult to say how these have established any claim to the Celtic connexion. The Sinclairs are Scandinavian. The patronymic Mac or its contraction M', which signifies son, will be observed to belong to about one-half the number.

The use of tartan or chequered woolen cloth is of great antiquity among the Celtic tribes. Originally, the costume of the Highlanders consisted of little else than a garment of this material wrapped round the body and loins, with a portion hanging down to cover the upper part of the legs. In Progress of time, this rude fashion was superseded by a distinct piece of cloth forming a philabeg or kilt, while another piece was thrown loosely as a mantle or plaid over the body and shoulders. In either case the cloth was variegated in conformity with the prescribed breacon or symbal of the clan; and hence the tartan was sometimes called cath-dath , or battle colours, in token of forming a distinction of clans in the field of battle.