"Horses and Hope"

The Morisons of Auchincrieve

George Morison, a Rothiemay farmer, travelled the North East in the late 1800s buying horses for the army. The Archive would like to thank Dianna Cameron-Shea for writing this article and allowing us a glimpse into the life of her great grandfather.

George Morison, a Rothiemay farmer, travelled the North East in the late 1800s buying horses for the army. The Archive would like to thank Dianna Cameron-Shea for writing this article and allowing us a glimpse into the life of her great grandfather.

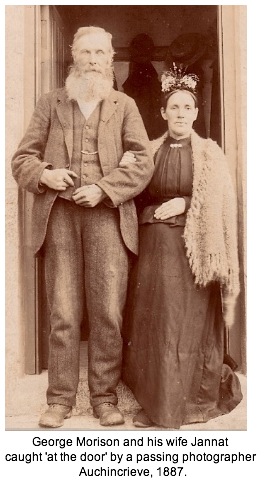

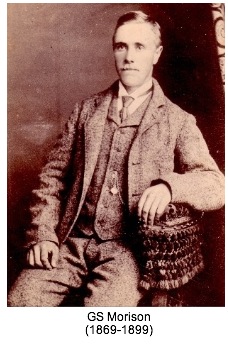

George Morison, shown here with his wife Jannat in 1887, was born in Banffshire in 1827 into a family of generations of farmers, whose particular interest was horses. George's maternal great grandfather, George Stables, farmed in the parish of Grange and also bred heavy horses for ploughing and forestry work. George inherited this interest in horses and horse breeding and, in turn, his eldest son, G S Morison, was reckoned, by others in the farming community, to be a skilled horseman and an excellent amateur vet.

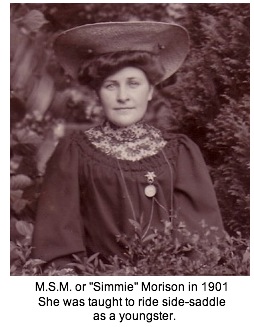

George and GS farmed roughly 78 acres just by Tarryblake in the parish of Rothiemay and produced arable crops as well as sheep, cattle and, in a small way, bred horses. The family kept three plough horses and one light harness horse which were fed on a diet that contained a special extra ingredient of George's own making. This diet - containing its secret ingredient - produced strong, capable, good natured animals with a great deal of muscle and staying power able to help them plough in all weathers and haul logs at the Tarryblake woods. The draught horses, one of which was called Peter, stood about 18 hands, had strong neck and shoulder muscles, a broad back and very powerful hindquarters. The harness horse, called "Meggie", pulled a lighter cart on the farm and was used, by George senior, to travel to outlying farms across the county on behalf of the Army, to view other farmer's horses that were for sale. At least one of the daughters of the Morison family was taught to ride side-saddle on "Meggie", quite a thing to do for a small rural farming family with no pretensions of 'grandness'.

During the 19th century Britain maintained a number of garrisons across the globe as part of the development, maintenance and control of the Empire. At one time or another, across this time frame, the State was involved in armed conflict too, either in these areas or in connection with incursions, by other foreign powers, into these areas which were regarded as part of Britain's overseas property. Equipment, guns, supplies and people were all moved by railway, horse and mule and sometimes oxen. Fighting was on foot or from horseback so the demand for horses, of all types, was high. This was before the mechanisation of the soldier that was to come with the Great War in 1914. The need for strong horses, such as the Clydesdales from Scotland was there, as was the need for the lighter horse that could sustain fairly high speeds under pressure.

The newspapers were full of reports on our Army's activities in Africa, Sudan, Egypt, Afghanistan and the North West Frontier, India, Turkey and many other places and the need for more men and more horses was a frequent question raised in the media and in Parliament. The ability of the Government to furnish the required animals for the work of 'policing' and for armed combat was frequently put to the test and there were 'questions in the House' as well as newspaper editorials. While much of Britain's fighting force was infantry, we also had 'mounted infantry' or 'mounted rifles' who would ride, then dismount and fight on foot.

George saw an opportunity to supplement the farm's income and to utilise the excellent skills of himself and his son as good judges of a horse and its abilities and so he made contact with Castlehill Barracks at Aberdeen, the Gordon's and the Depot Battalion home, to ascertain if his services as a "broker" would be useful to the Army. Obviously it took some time to convince the Commander that he could do what he proposed, that he could supply a number of horses of good quality at the price established, but, "ever the businessman", once the deal was struck George set to with a will.

When he got the go-ahead he set about a programme of attending markets to look at mares and geldings for sale, meeting other farmers there and talking to them about his interest in horses that they may have had for sale; and through his other contacts with people both locally - and through the family network across Banffshire - he made a number of connections that meant that he had a steady supply of animals. He travelled as far down as the Borders to search out particular types of mount.

It seems odd to us, today, that there was not some 'national' supply of horses for the Army. We have become used to everything on a larger scale and requirements for motive force, now tanks, armoured vehicles etc being a supply contract between the manufacturer and the MoD. Strange to report the purchase of horses and what were called 'remounts' were the responsibility of individual regiments and their respective commanders. In 1887 the Army decided that this should stop, that it was not a very regular method of supply and so a centralised 'procurement' facility was set up so that, initially, regiments stationed here in the UK drew horses from the central pool. To accomplish this many more people like George Morison, all over the UK, were encouraged to register their available horses with their local garrison.

The need too to ensure a steady supply of horses meant that more horses needed to be bred. A Royal Commission was established in 1888 to enable grants to be made to individuals who owned good quality stallions. George and his son were thus enabled to obtain grants for breeding and the future looked very bright for them, the family and the farm. George, by then losing his sight, looked towards handing the farm over to his son and his wife-to-be. Then disaster struck. GS had suffered for some time from emphysema, most probably as a result of farm work with hay and other cereal dusts, and had been out with the horses and equipment. An accident occurred and, as far as we know, he cut the horses free but lay out in the outlying fields in awful weather for many hours. By the time the family found him he was suffering from hypothermia and subsequently developed a chest infection. There were no antibiotics then, even sulphur drugs were not in common use, and so his family could only watch, wait and pray for him to recover. He never did. GS died on 25th January 1899 as the result of pleurisy.

So came to an end the story of a farm, a farmer, his son, and their hopes for a horse breeding business that would ensure their future and that of their descendants. George, losing his sight and his zest for life, left the farm with is wife and one of his daughters and another son and moved to a cottage in Rothiemay. He died in 1911.

___________

ęDC-S

Sources:

Morison Family papers ęDC-S

Aberdeen Journal editions 1887 - 1900