The Land

Farming in Banffshire, 1905 and 1913 – 1916

From a series of articles published in the Banffshire Journal, beginning in December 1994, by historian Andrew Mason.

The Diaries of George Wilson

Grieve at Bowiebank Farm and Farmer at South

Colleonard. Reproduced for the North East Folklore Archive courtesy of

the Banffshire Journal.

Grieve at Bowiebank Farm and Farmer at South

Colleonard. Reproduced for the North East Folklore Archive courtesy of

the Banffshire Journal.

Historian Andrew Mason came across the diaries, which he describes as "a nationally important and unusual find", during a visit to South Colleonard, by Banff, in 1994.

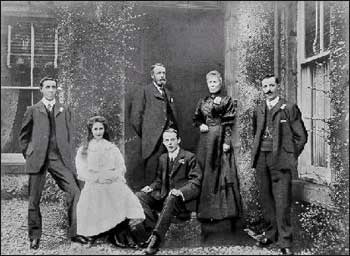

The Wilson family at Bowiebank

"I saw a pile of journals stored in the bottom of a cupboard. Inquiring, I was told that they were old farm diaries. Detailed examination revealed a collection of diaries, predominantly written by George Wilson, father of the present owner of South Colleonard, [now the late] Robert Wilson.

One of the primary purposes of the study of history is to research the records of the past in an attempt to understand better both the past and the present. The farm diaries of George Wilson, grieve on the farm of his father, Robert Wilson, enable us to do that. For this opportunity I am deeply indebted to George Wilson for writing the diaries, and Robert and Laura Wilson, South Colleonard, Banffshire, for allowing me to research and quote from them."

Andrew Mason, Banffshire Journal, January 31st 1996.

PART I: BOWIEBANK FARM, 1905

Fine weather sees the planting of many forgotten varieties

Banffshire in the summer of 1905

Hay stacks spring up as the "Hairst" moves on

When the Horseman reigned supreme

PART II: SOUTH COLLEONARD FARM, 1913 – 1916

The farming diaries of George Wilson, grieve at Bowiebank, run from 1903-1913; the family having occupied the farm since 1895. The usual farm lease of the time being 18 or 19 years, its expiry in 1913 brought about great changes for the family. George's father, Robert Wilson, retired from farming at this time and removed to Cults. George Wilson was to be the farmer, not the grieve, with a farm of his own. For this, he also removed from Bowiebank and crossed the River Deveron to settle at the farm at South Colleonard.

War spreads change around the country

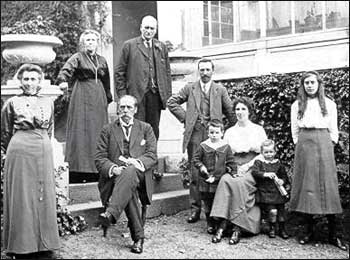

The Wilson family and friends at South Colleonard, c1914

PART I: BOWIEBANK FARM, 1905: January 1905

The farm of Bowiebank nestles

on the eastern side of the Deveron, some four miles south of Banff; the

horizon is dominated by the ruin of Eden Castle, once a  stronghold of the

Meldrums and later the Leslies. It is now forlorn and abandoned, guarding

the Deveron Valley and the southern approaches to Banff against enemies

long since departed.

stronghold of the

Meldrums and later the Leslies. It is now forlorn and abandoned, guarding

the Deveron Valley and the southern approaches to Banff against enemies

long since departed.

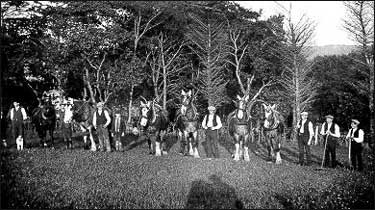

Farm workers at South Colleonard circa 1916

The farm of Bowiebank had been part of the Fife Estate, and the land was

farmed by Robert Wilson. The estate had been contracting throughout the

last part of the 19th Century, and having recognised the diminishing rentals

from land of the agricultural depression, the estate had been steadily

selling off land and was now reduced to the core holdings surrounding Montcoffer.

Robert Wilson farmed nearly 400 acres at Bowiebank in 1905. The diaries

kept by his son, George Wilson, from 1903 to 1913, record the daily working

of that farm and provide a magnificent insight into farming in Banffshire

at the beginning of this century - a century of unprecedented change

in the structure and methods of farming, which have transformed the countryside.

In 1913, George Wilson took up the lease on the farm of South Colleonard, a Fife Estate farm. The diaries continue from 1913 to 1965.

The farm of South Colleonard was taken over by George Wilson's son, Robert Wilson, and is still farmed by the Wilson family today. Robert and Laura Wilson occupy the house of South Colleonard, and the diaries were in their safekeeping.

The presentation of these diaries is entirely due to the generous help and information provided by Mr and Mrs Wilson.

The diaries are purely farming journals, recording the work and rhythm of the seasons. Other aspects of life do not impinge upon their pages. Wars come and go without comment, save when they affect the farm, the work or the men.

Detailed reading of the diaries, supplemented by conversation with Mr Wilson, indicates that Bowiebank as a substantial farm of that time. It was managed by Robert Wilson, with his son George acting as grieve.

Next in the hierarchy of the farm came the ploughmen, each man responsible

for a pair of horses.

Next in the hierarchy of the farm came the ploughmen, each man responsible

for a pair of horses.

Bowiebank was a three-pair farm. With this number of horse pairs on the farm there were substantial numbers of other tasks to be performed that could not be undertaken by the ploughing pairs, and the "orra" man, with his single "orra" horse, was an train for Ross of Ballindalloch. (A quarter of grain is equal to three hundredweight)

The weather of January, 1905 was changeable, with frost and stormy days along with fine days, and work of the farm continues in line with the weather; ploughing and driving turnips when possible, and thrashing oats and taking in straw on stormy days.

Emerging from the pages of the diary is a pattern of life that is no longer easy to visualise for those who have not encountered it. The pace of the farm was geared to the pace of the horse, be it working in the fields or making deliveries to the local stations. The speed of the horse was central to the life of the farm of Bowiebank.

On the other hand, the train and the local stations are an everyday part of the farm life, linking the farms with the regional and national markets to augment the purely local one.

The pattern of farm life in January 1905 is more complex than the usual image of a more leisurely era with a slower pace. That is only part of the story - another part is of a farm that formed a link in a larger economy, bound together by a train network that served the community through the local stations.

George Wilson saw March 1905 come in like a lion.

The weather of the last week of February had been fine, with the last two days of the month being recorded by George as "soft".

Wednesday, March 1, was, however, described in his diaries as "stormy". The men were busy, collecting 24 bushels of draff [remains of barley after fermentation [cattle feed] from Banff Distillery. Collecting draff from the local distillery was, as was noted in February, a practice new to Bowiebank, and probably one that George Wilson helped to introduce along with his father.

The use of the draff seems, from the diary entries, to be successful, as the men are sent to the Banff Distillery twice more during the month, on the 15th and 22nd, for another 24 bushels each time.

The other regular tasks of this first day of the month at Bowiebank were carting turnips and ploughing. Working with turnips, pulling, carting and driving them either to the sheds or, predominantly in March, to the sheep, took place on 21 days out of the month.

It is interesting to see this level of activity devoted to a crop that only 150 years before had hardly been known in the county.

The shorthand term that historians use for the re-shaping of the landscape of Britain during the 18th century is the Agrarian or Agricultural Revolution.

As with all such shorthand terms, it is not a definition in itself, and debate continues as to whether the 18th century is an adequate boundary for the changes that were underway in agriculture and whether using the term "Revolution" to describe the changes is helpful or only a distraction.

Such debates need not detain us at present; what is important is that the last famine, as such, occurred in Scotland at the end of the 17th century, now often referred to as the "seven ill years" or "King William's ill years".

Considerable changes in the 18th century combined to eradicate famine. Principal among these was the development of agriculture and the introduction of new crops, including the turnip, as both the turnip proper and the swede were introduced. The root referred to throughout this document as the “turnip” is the swede.

Root crops, such as the turnip, were virtually unknown in Britain before the 18th century. Introduced into England from the Low Countries - present day Holland and Belgium - they provided one of the staples that enabled stock to be over-wintered. Before their introduction, the majority of the stock was butchered each autumn and salted down for winter consumption. The few animals that were kept over the winter had to get by on such little feed as was available and emerged each spring - those that survived - thin and wasted from hunger.

Early spring feeding returned the stock to size and then the round of breeding began before the late autumn saw the older and surplus stock butchered and salted for winter use.

Writing in 1797, the Rev Abercromby Gordon, Minister of Banff, says: "About 40 years ago, potatoes and turnips were cultivated as rare vegetables, in the garden, and were not brought to market. Now, cattle are chiefly fed by turnip..." (Old Statistical Account).

Tales of the turnip as a garden crop and exotic abounded in the 18th century. One of my favourites is the serving of turnip as a dessert! As a new and rate exotic, the uses that the turnip could be put to were generally unknown, and before it became widely available, hostesses would impress their dinner guests with desserts made from this "rare and expensive delicacy".

Carting the turnips to the sheep was a considerable part of the farm work during March. The amount of loads of turnips taken to the sheep on a daily basis vary between 10 and 20 loads on a single day, often with 14 loads being followed the next day by 20 loads. This amount of turnips taken to the sheep would indicate a considerable holding. Unfortunately, the diary does not give the total number of sheep at Bowiebank. Further hints, however, are available from George Wilson's diaries.

Thursday, March 23, is the first entry recording the provision of oats for the sheep, with half a quarter being given. On the 27th "2 bushels corn to sheep" is recorded, followed on the 28th by "2 bushels to Shepherd" and again on the 29th "1 qtr oats to Shepherd" with a final "half qtr Oats to Shepherd" on March 30.

From that evidence it would seem that the flock was of sufficient size to warrant the designation "shepherd" for the farm worker in charge. The other conclusion to be drawn from the introduction of oats and corn to the ewe's feed in late March is that lambing was imminent.

Of the other livestock, the sow is taken to Montcoffer on March 11, served on March 13 and returned on the 18th. The previous litter being sent to Turriff Mart on the ninth, being 12 young pigs and averaging 17/6 (87p) each.

Ploughing had been recorded throughout the month as the weather and condition of the land allowed. On March 23, George Wilson records "break in bean ground. Sow beans, 1 qtr. Plough them in".

The spring tooth harrow having gone to Keilhill Smith on March 10 is returned and put to work as the entry states: "Break in Yaval with spring tooth harrow". The previous week, 34 half quarters of oats have been dressed; 20 quarters for Mr Shand, Northwells, Rothie, and the rest for Bowiebank. Mr Shand's oats had been driven to King Edward Station to await the train.

On Tuesday, March 28, the diary says: "Commenced sowing in Scotston field Lea, 9qtrs" and later in the same day's entry "Sow Castleton oats, 8 rigs from road, top half'. And the next day: "Sow middle half with Knochiemill, 14 half quarters".

Three new men had joined the farm that March. On the 7th the diarist had been at the market in Turriff and engaged W. Middleton at £33; A. Innes at £29 and Wm Barron also at £29 for the year. By the middle of the month he gives Peter Seivwright an advance of £5 of his wages.

March has been a busy month at Bowiebank; new men to replace those who had left; lambing had begun; four calves had been born and the spring sowing was underway.

Having come in with the lion, March goes out with the lamb, literally, with the onset of lambing and figuratively, as the weather of the last week all being described as "fine".

This is confirmed by two entries. Although not specially recorded as the first lamb of the year, the first lambing entry from the diary is on Tuesday, March 14, with "ewe lambed one lamb" and this if followed on the 30th with a more satisfactory "ewe lambed three lambs".

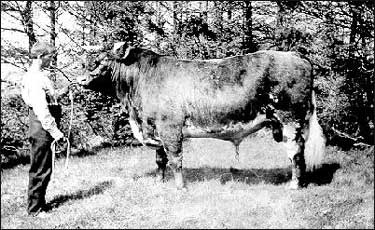

March also saw the arrival of other new additions to the Bowiebank farm stock. On the 3rd "Queen Cow calved a Black Bull calf with white socks" while on March 5, a Sunday, "Blanche Shorthorn Cow calved a Red Bull calf".

The only entries to be recorded in the diary for a Sunday are those dealing with calving, no other farm activity is recorded, although the normal stock work had to continue.

Two more cows calve: "Hillhead Shorthorn Cow calved a Roan Bull calf" on the 27th and the "Red Yearling Heifer calved a Heifer Red calf" on March 30.

In addition to this natural increase in the stock levels, a Stirk is purchased from John Taylor at the Mill of Eden for £5 10 shillings [£5: 50p].

April 1905, then, as now, a changeable month, with the green shoots showing on the otherwise bare trees, began well with "soft" days.

Saturday, April 1 had the men of Bowiebank busy with half quarter of oats to the shepherd as well as thrashing another three quarters and harrowing are also recorded but we are not told in which fields. The round of pulling and driving turnips continued.

The first barley sowing entry of the year is also started on the 1st with the entry "Sow Little Castle field with barley from Segget Maltson one half quarter."

Whilst this is underway, another of the workers is dispatched to the station at King Edward to collect three quarters of barley from Mr Shand at Northwells and "five quarters Oats Hamilton from Musselburgh."

The continuing quest to find and bring into production the best of seed that was available from all over Scotland, whilst selling their seed to other farms, usually further north, always with the aid of the national network of railway stations, had created and was developing a national agricultural economy.

Sunday was, as usual, the day when the diaries were silent apart from the arrival of new stock and on Sunday, April 2, the "Black Horned cow caved a Red Bull calf." That week was busy with the arrival of new stock with Monday's entry having the "baby cow calved a Red Bull calf" and on Tuesday "Mary cow calved a Black Bull calf."

Having received the barley from Mr Shand on the Saturday, it is sown in the Haugh on the Monday. The ground of the cross rigs in the Haugh having first been broken in with the spring tooth harrow, the sowing accounting for two quarters, six bushel of the three quarter collected.

Amongst the daily entries of this busy time of the 1905 farming year is a curious one concerning the sheep on the Bowiebank farm. On Monday, April 3, it simply states that the "sheep left us". Quite why the sheep leave the farm in April and where they go to, the diarist does not comment. Presumably, they were only over-wintering at Bowiebank and as soon as the land was required for the spring work the flocks were taken off the land and moved to other farms nearby to finish off the bulk of the lambing.

The last day of good weather at the beginning of the month was Tuesday, April 4 and amongst the other farm work was the entry that had "baby second sold at Turriff Central mart (now no longer standing) for £15 17s 6d." It is from entries such as this, when cattle were given a single price, that comparative figures can be gained from the diaries between then and now.

The next week the diarist is again at Turriff, this time with four cattle which sold for £80 7s 6d. He returned with three store cattle but does not say what he paid for them.

The 5th to the 10th of April were recorded as stormy and bad days with snow and the spring work on the land was halted and the men given over to indoor jobs or preparatory work for when the weather should break.

A stack was taken in on Wednesday, April 5, the first day of the weather breaking, and four half quarters were thrashed. Oats were also dressed for seed and the third pair taken to the Dunlugas Smith, presumably for shoeing.

On the Thursday, a day of snow, the first pair are at Dunlugas along with a "young horse getting on hind shoes." A cart is sent to Banff Harbour Station with six quarters of oats for James Scott, Barry. A reminder that whilst the railway network was national, it was not always possible to ship goods from the nearest station, King Edward.

Bulky goods, such as the “six quarter” of oats, would have to be manhandled from train to train, a time consuming business and were dispatched from the station that had the best connection with the desired destination. Whilst at Banff, the cart also dropped off one quarter of barley to the lime Company and brought home one hundredweight of Linseed Cake [the remains of linseed after the oil has been extracted - cattle feed].

Those men working at Bowiebank were dressing oats for seed and when they ran out of things to do were put to sawing firewood.

Another cart was dispatched to King Edward Station, this time for 10 hundredweight of "cakets" and one quarter of Rye grass seed, from Dumfries.

The diary indicates that the produce both imported and exported to and from Bowiebank were often directed to and from specific individuals and not being marketed through merchants, such as Robertson's of Banff or the Lime Company.

The remaining days of bad weather were predominantly taken up with driving out dung and thrashing the stack that had been taken in. Two more stacks remain at Bowiebank and these are both taken in during April.

The turnips are being lifted and driven up to the Mains during the month often in considerable quantities on a single day. Wednesday, April 12, for example, has 50 loads of Swedish turnips being taken to the Mains for the cattle.

Before the advent of mechanical lifting the sheer physical effort involved for both men and horses in tasks such as these is hard to grasp.

The effort to be among the top farmers in the area can be seen again in the entry "manure delivered." The quantities involved are considerable and probably mean that Robertson's in Banff had sent out the steam locomotive and trailers with the load and that Bowiebank Farm was mixing its own manure.

The weather continued fine for the remainder of the month and the spring sowing of oats, grass, barley and some of the beans was completed by the end of the month. A long month of hard work at Bowiebank, with fine weather, had accomplished all the grain crops by April's end.

PART I: BOWIEBANK FARM, 1905: Fine weather sees the planting of many forgotten varieties

The Deveron Valley and Bowiebank Farm must have been a fine sight in the

spring of 1905. No "teuchat storm", nor "gab o' May" that

year.

["teuchat storm": bad weather when the "teuchats" (lapwings)

are nesting.]

["gab o'May": bad weather after mid May.]

The diary entries of George Wilson throughout the month, with only two exceptions for showers and one of soft rain, read fine day, following fine day.

The diarist records starting the month by sowing beans in the Haugh but the work at Bowiebank that first day of the month was well up to date as the farm is also able to lend out its second pair of horses to a neighbour.

Also that Monday begins the work of potato sowing with 51 bushels being made ready for seed. The varieties and quantities sown were as follows: 20 bushels Brit Queens; 6 bushels Champions; 6 bushels Up to Dates; 5 bushels Main crop; 5 bushels Sutton Abundance; 6 bushels Factor; 3 bushels Lady's Favourite. I wonder how many of these varieties are remembered today and if, in fact, any are still growing?

Those first weeks continued with preparation for the sowing and care of the potatoes and later in the month the bulk of the turnip sowing. The men were grubbing the ground and latterly harrowing with the spring-tooth harrow.

The destruction of weeds in 1905 was a problem for Banffshire farmers who did not have today's range of chemical treatments available. The diary records the grubbing up and carting of weeds off the land. Conversations with the diarist's son, Robert Wilson of Colleonard, on this and other aspects of the diaries, reveals that the weeds were grubbed up and collected for carting back to the farm. Here they were gathered up into heaps and then trenched with hot lime to destroy them. The carting of the weeds continues during the first two weeks of the month.

A week after their first planting of potatoes commenced the second, a smaller one. This time the varieties were Ridney Beauty; Champion and Suttons Abundance. This Monday of the second week of the month was also the day for planting the farm's cabbages and kale.

The first two weeks of the month were busy ones for the stock with movements both off and onto the farm, as well as the natural increase. It was the natural increase that gained the first entry for May 1905, with a black heifer calving a black heifer calf.

The following day at Turriff Mart, four cattle were sold at a price of £88 2s 6d whilst four were bought, although there is no price recorded for this purchase.

Robert Wilson also informed me that cattle tended to be kept a year longer

for fattening at this period than is now the case, adding significantly

to the costs but also producing a larger animal.

The

following week, again at Turriff Mart, saw the sale of four more cattle,

this time for £74 5s and four were bought at the mart.

The

following week, again at Turriff Mart, saw the sale of four more cattle,

this time for £74 5s and four were bought at the mart.

George Wilson and his father Robert of Bowiebank were well known for their shorthorn cattle.

There were two sales locally also held in these first two weeks of May 1905; one at Rotherwood yielded two fat cattle, whilst the other at Bush produced two colts, this time with the price of £50 10s given along with the entry.

By mid-month the potatoes are all planted, the weed gathering is well underway and dung is being carted to the fields.

A shortage of hay results in a journey for one of the hands to the Mains of Blackton for a load which is curiously recorded as being "82 stones".

The second half of the month starts with a most useful piece of information - a recipe for making manure on the farm and the quantities required per acre:

1cwt bone meal; 1cwt SB flour; 1 Supers; three-quarter cwt. sulphate of ammonia and half a cwt. of potash salt to the acre. This manure is mixed and then spread the following day at the start of the turnip sowing.

Again the diarist records the turnip varieties used starting with "commenced to sow Swedish turnips, Aberdeenshire Prize Purple Tops, 36 drills." This was followed the next day by the balance of the sowing of the Aberdeen Prize adding another 24 drills.

The next day a hand is dispatched to Gellymill with four half quarters of oats for meal whilst the sowing continues, this time with "Gales Champion Swede, 58 drills". Sowing continued on a daily basis with the Gales being finished the following day and the Best Of All Swede sowing started.

By May 20, along with the daily sowing, continued the driving of dung to the drills and the closing of the drills after dunging, two more sowings, this time of 13 drills of Early Yellow and another 18 of Best of All.

During the respite in sowing another trip to the Turriff Mart produced two heifers and two stots [steers] for the farm; whilst the Dunlugus Smithy is called on to provide shoes for "Brish" and slippers [first shoes, often timber] for a colt.

The last week of the month saw the restarting of the turnip sowing, a

busy time on farms all over Banffshire. Friday, May 26 records: "At

Brandons Fair."

The

hiring fairs of agricultural workers were held in May and November, at

which point those who wanted to move onto another farm or whose services

were no longer required, would attend the fairs where, hopefully, they

would be offered employment for the next six months by the farmers.

The

hiring fairs of agricultural workers were held in May and November, at

which point those who wanted to move onto another farm or whose services

were no longer required, would attend the fairs where, hopefully, they

would be offered employment for the next six months by the farmers.

George Wilson, standing second from right, with his farm hands

These gatherings filled the streets of the towns with farmers and farm workers of all kinds seeking work and workers as well as meeting and trading information and stories.

The six-month contract for agricultural workers was an outcome of the creation of the farms from the earlier "ferm touns" and the considerable mobility it offered farm workers had considerable social consequences in the area in both the 19th and 20th centuries.

George Wilson does not record how many workers leave Bowiebank or who they were, but he does record those engaged; Frank Ewing, cattleman, £16; Alex Sheriff, third horse, £15. It is interesting to note the wage differential between the two workers and it is a reflection of their different skills and status in the farming hierarchy. George Wilson also attends the Porter Fair but engages no other workers.

On the Monday following the fairs, the central role that the railway network played in Banffshire at the beginning of the century is again demonstrated with the entry, "Went for flitting to King Edward Station."

By Tuesday, May 30, 1905, the new workers would be settling to their new farm and George Wilson is again off to the Turriff Mart, this time with six stots [steers] which he sells for £19 10s each. Meanwhile, he has sent to "Robertson's of Banff" for more ingredients for his manure. June was undoubtedly going to see more turnip sowing at Bowiebank.

PART I: BOWIEBANK FARM, 1905: Banffshire in the summer of 1905

Banffshire was, for the most part, warm and dry.

June was a very dry month; dry enough to raise concern with the diarist as the month progressed. The early entries that accompanied the sowing of the late turnips refer to "fine day". By the 6th, this has changed to "fine day but dry" and as the weather continued unbroken, there are signs of alarm as by the 10th the entries record the weather as "very dry". By the 16th: "Very warm and greatly in want of rain", a line from 90 years ago that will strike a chord this year also. The remainder of the month continues, with only two exceptions, as warm and dry. These exceptions that brought rain seem to have been sufficient to allay the foreboding of the diarist as there are no more pleas for rain in the record of the summer months. July is mostly fine with some showery days and by August, the record states that most of the days are "soft", with a "stormy day" on the 24th and a "very bad day" on the 26th. By the month's end, the weather has again moderated and August ends as it began with "soft" days.

The first days of June were taken up with sowing the residue of the turnips; "Bullock yellows", "the Challenger", "Stroba Blue", and "Kerr Improved Purple Top". These were usually sowed 54 drills at a time; that seeming to have been the daily amount recorded. Simultaneously with the sowing entries, the dung from the yard is being driven out to the turnips.

The last of the turnip rows were sowed on the 7th June and between the 8th and 12th the end rigs were ploughed, prepared and drilled; dung was carted and the drills were closed.

With the potatoes and turnips safely in there was a brief interlude before

the crops would again require attention and the days of mid-June were taken

up with gathering brushwood; 11 loads to Home Farm and 10 loads to the

cottars being collected and cared in two days. There was also time to hire

out men to the neighbouring estate of Eden, with two men and pairs being

recorded as working for five days, 10 hours each day, driving sand to Eden;

during each 10- hour day they managed 32 loads. No small undertaking as

each cart would have to be loaded and unloaded by hand. Their week at Eden

finished with them carting sticks for the final day.

Whilst two men and their pairs were away at Eden the other pair and the "orra" man

and boy were engaged in cutting the thistles and ragweed in the cornyard.

The cornyard was then tidied and the carts washed. This washing of the

carts seemed to be an annual convention at this time in June, as no other

mention of cart washing occurs throughout the rest of the year. By the

third week, the respite from the crops is over and on 22nd June are the

first of the entries that are set to dominate the diary; "Shiming" and "Commenced

to hoe Yellow turnips". "Shiming" is the cutting of the

weeds in between the drills of turnips and hand hoeing was the principal

method of weed removal from around the plants themselves. A long labour

as anyone who has ever done any will tell you.

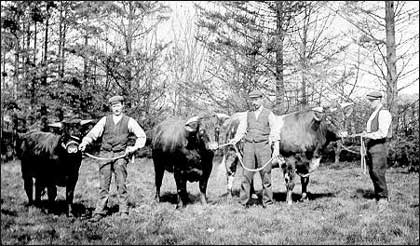

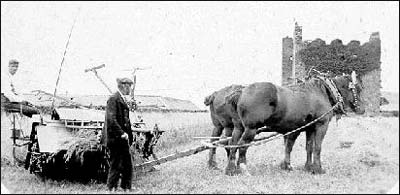

Robert Wilson supervising work near the ruins of Eden Castle

In 1905 the first hoeing lasted 17 working days, from late June until mid-July. The entries following on one from another "hoeing" and finally "finished hoeing" on the 12th July.

George Wilson records only two days break from the repetition of these days until on the 14th come the entry "hoeing and shiming the second time". This second hoeing lasting 15 working days but this time not, as the sole farm activity.

The second hoeing coincided with the hay making, when cutting started on Monday, 17th July. By the Thursday, the hay was being turned and on Friday, 21st July, 196 stones of hay are driven to Eden Stables; unfortunately, I'm not sure how much hay 196 stones represents or how the farmers of 1905 were able to quantify hay in this manner.

The work with the hoeing and the hay continues for the rest of July; the hay being ready to be "put up" at Bowiebank on the 7th August and "put up in field" the following day. By 11th August, work with the hay is finished, nearly three weeks after the first cut was taken.

Shows were very much part of the farming year, and George Wilson attended the Banff Show with a horse, unnamed, and a shorthorn bull and got a second and two thirds, on Sunday, 29th July. The following week, on August 1st, he is a Turriff Show, but with no record of any entries this time.

By mid-August, the hay safely "put up" and the weather still holding fine, it was time to start the harvest and to collect the winter coals from Robertson's in Banff. Monday, 14th August and the carts are trundling along the road to Robertson's coal store at Banff harbour to collect 67 barrels of coal; with another 21 barrels the following day. This was then distributed amongst the workers at the rate of 30 hundred-weight for Wm Middleton, Alex Innes and Wm Barron and 22 and a half hundred-weight for Wm Gardener. A supply of coal was often part of the hiring terms and it may well be that the terms of a gardener warranted seven and a half hundred-weight less coal than for a farm worker; it can hardly have been that his fire burnt less fuel.

The 14th August was also the day to commence the harvest in 1905; on the

15th they "Commenced to cut with Binder", and by the 16th Alex

Clark, Kintore, had been engaged for the harvest at £5.

The 14th August was also the day to commence the harvest in 1905; on the

15th they "Commenced to cut with Binder", and by the 16th Alex

Clark, Kintore, had been engaged for the harvest at £5.

The progress thereafter was more rapid, the next day seeing the Scotston field being cut with two binders: but even with his doubling of binders the field took two days to cut. The "Lea" and the "Yaval" fields were cut next whilst the weather held; though some men were put to "raking."

Three days were spent cutting the "Yaval" before the weather and presumably one of the binders broke; there being the entry "Received fingers of Binders from Seller, Huntly" on the 22nd. The weather breaks to a stormy day on the 24th, which is spent in "cutting the lying corn" and in "cutting roads round the barley in Haugh" and in raking.

The weather again turning "soft" the following day, they return to cutting the "Yaval", with the "Black Corn" commenced. The weather again breaks on the Saturday being a "very bad day" and the men are put to "setting up stooks" and to "twining rapes" and "Cutting broom for stacks".

Monday, 28th August is also "very wet" and the day is spent in "Cutting broom and whins" and in "driving them", whilst the following day is given over to "setting up stooks". By the Wednesday the "Yaval" field, the "Cornyards field" and the "Black Corn" are all cut, and the cutting starts in the "Haugh", continuing on the Thursday, 31st August.

On Friday 1st September comes the entry. "Finish cutting Barley also lying hole [part of field where crops lie down due to damp ground] in Lea field", followed on the Saturday with "finish cutting". The first part of the harvest for the year was complete: the first load of the new corn was taken to the thrashed on 31st August.

PART I: BOWIEBANK FARM, 1905: Hay stacks spring up as the "Hairst" moves on

The fine weather continued into September, and the harvest was drawing to close at the beginning of the month, with the cutting being finished on the second.

In 1905, the equipment used for cutting the grain was two-fold: the binder was the main mechanical tool in use at Bowiebank, while the lying grain was cut by hand with the scythe. Reapers had been in use on the farm and were still available but the diary of 1905 makes no mention of their being in use that year, although they were recorded as being stored at the close of the season.

The use of binders was still in its early stages and from August entries it was apparent that these machines required attention to be kept at the cutting. "Sellars' man" was "at Binders" the day after the cutting commenced on August 15. Two binders were then put into use but by August 22 new fingers from Sellers of Huntly were necessary and by September 1st the diarist records that he had to go to "Macduff for sail had old one down to be repaired". This the day before cutting was finished for that year.

The binder was the next stage in progression

from the reaper. This machine had a cutting bar followed by cantilever

slats to form the sheaf. The Sheaf was then bound with a band of twisted

straw. This process had been performed manually, the motive power being

the operator's feet. In the reaper, following the cutting bar, was a canvas

that revolved clockwise and one anti-clockwise. From this, the crop came

up to the packers where the sheaves were tightened and bound ready for

lifting into stooks.  The corn that was in the "lying

holes" had to be cut by hand, usually with a scythe, a job for a wet

day or when the rest of the field was cut.

The corn that was in the "lying

holes" had to be cut by hand, usually with a scythe, a job for a wet

day or when the rest of the field was cut.

The “Back Delivery Reaper”. The crop is cut and when the horseman decides the bundle is big enough to make a sheaf he operated a lever, which left the bundle on the ground to be tied manually into a sheaf. The sheaves were then built into a “stook” of six sheaves and left to dry. George Wilson stands to the left of picture while a young girl makes a corn dolly from straw.

The cutting finished on the Saturday, the entry for Monday has the men "hatching hay stacks" whilst George Wilson goes to King Edward: "At King Edward for beer", the harvest ale.

The haystacks thatched on the Monday had their thatch cut and trimmed on the Tuesday whilst six cattle are driven to Turriff Mart. No prices are recorded, indeed there is no record as to whether a sale is made, but one presumably is, as on the Wednesday George is back at Turriff to collect 120 lambs and six ewes. Five of the ewes he sells to J. Duff of Bruntyards but the remaining one and the 120 lambs have to be driven back from Turriff to Bowiebank. There is no record as to how the journey went.

Whilst George is at Turriff, the stooks from the lea field are started to be led back to the farmyard. The leading out continues for the remainder of the week, during which the weather remains fine. Even so some of the stooks are shifted about before being led out.

Four days are spent leading off the lea field and the barley field to the Mains and by Monday, September 11, attention has been turned to the Yaval parks. These are completed in two days and are followed by the cornyard field, in one day, and the Haugh, two days, the leading of the stooks being completed on Thursday, September 14.

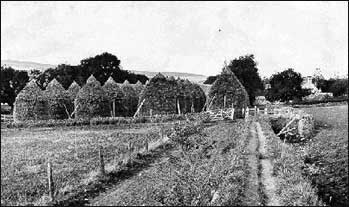

The harvest of Bowiebank in 1905 consisted of 22 stacks at the Mains and 26 stacks at Bowiebank. These circular stacks would usually be built up on stone foundations that were often a semi- permanent feature of the cornyard. They were usually two feet off the ground and about 12 feet in diameter.

Building a Stack:

The method of building a stack varied from farm to farm and from individual

to individual but one method was to start with about six raised sheaves

in a circle in the centre of the stack. From these the sheaves were arranged

outwards in concentric circles, always taking care that the centre of

the stack was "hearten" or raised, to shed the rain outwards

from the stack.

The stack was then built up in heightening concentric rows from the raised

centre by the farm workers who knelt on the completed stack as it rose,

whilst another worker was on the cart forking sheaves to the stack builder.

The work of this stack builder caused considerable discomfort and he

usually wore an old reaper canvas or canvas bags around his knees whilst

he worked. Sometimes an older worker was available to act as a guide

from the ground, shouting instructions to help keep the sheaves in line

as the stacks rose.

The work of this stack builder caused considerable discomfort and he

usually wore an old reaper canvas or canvas bags around his knees whilst

he worked. Sometimes an older worker was available to act as a guide

from the ground, shouting instructions to help keep the sheaves in line

as the stacks rose.

The corn-yard

The harvest of 1905 consisted of 48 stacks, a good harvest for the period.

The stacks built and the rakings taken in, the steam mill arrived on Saturday, 16th. It stayed for only half a day but in those 41/2 hours they were able to thresh 581/2 quarters of oats. These were mostly for use on the farm but Bowiebank also supplied the stables at Eden House with two quarters.

The beginning of the following week was taken up with finishing the thatching of the stacks and in horse raking and taking in those rakings, leading to an entry on Wednesday, September 20, "Finish harvest in five weeks". A short harvest indeed and one aided by the run of fine weather.

The extra harvest hands, John Robertson and Alex Clark, were duly paid off, £6.7 shillings to Robertson and £5 to Clark. There is no mention of their "harvest beer", fetched from King Edward, being drunk, but no doubt it was.

There was, however, no let-up in the work now that the harvest was complete. The first potatoes, "British" were lifted on the Wednesday whilst other workers moved to cutting the rye. This is the only mention of rye in this journal and it is probable that a small amount was grown, not primarily for grain but for straw. This was used predominantly by saddlers for stuffing horse harness and saddles, being better for the purpose than oat or barley straw.

As September draws to a close, the weather remains fine throughout. The binders and reapers are inspected, repaired and put away for the season. Some workers are lent out on individual days to other neighbouring farms to help with the steam mill, whilst, for those remaining, the ploughing begins on the 22nd of the month. "Pull and drive turnips" is recorded next day.

The last week of the month and the round of ploughing is now entered into. Every day's entry in the diary has some of the farm workers ploughing, whilst others are engaged in pulling turnips. Cutting the potato "shaws" [leaves] with scythe occupies this last week.

Other jobs of the season include cutting down some trees and taking them to the carpenters; collecting timber and the sawdust from previous loads. Sawing firewood and bruising and thrashing small quantities of oats with the farm mill now fill the pages of the diary.

Tuesday, September 26, saw two ewes bought at Turriff Mart for £5 12 shillings, and three colts taken to Dunlugas Smithy.

The harvest completed in such good time the farm moved quickly and without respite onto other major tasks. The ability to lend out workers for days to the steam mill and other tasks, such as tree felling and firewood cutting that some of the others had to do, provides a note of relaxation towards the month's end.

PART I: BOWIEBANK FARM, 1905: Stormy October

The new month brought with it the autumn equinox and a change in the weather. The long summer of 1905, with the early lack of rain that had so worried George Wilson during sowing, had been a year of fine dry days, almost without a break. A good harvest had been produced in five short weeks, ending in mid-September.

Monday, October 2, and the first working day of the month heralded the change, with the entry "Cold and Stormy". The remainder of that first week was "very cold and wet" or "stormy" and "blowy". The change in the weather did not, however, signal a changing of the seasonal work of the farm of 1905. The diary entries of that first week are a reflection of the last week of September, with the ploughing being the main task of the season.

Without the benefit of any shelter at all from the elements, the ploughman and pair must have had a miserable existence during those "cold and stormy" days of early October, exposed on the hillsides of Bowiebank, following the plough for a full working day.

The only concession to the weather during that first week seems to have been the entry "liming back byre", an indoor job for some of the farm workers on the first day of the stormy weather. Although not a job without its hazards in 1905, the lime used not being hydrated lime now readily available but slaked or "hot" lime which, as its name implies, sets up a reaction when mixed with water. The resulting mixture spat and bubbled in the mixing bucket, and often all over the men doing the mixing.

Otherwise, the ploughing continued, as did the cutting of the potato heads and the pulling and driving of the earliest turnips. By the first Friday of the month enough of the potato heads had been cut to enable the men to gather up the potatoes in the drills ready to be taken up. Fortunately the Saturday was the only fine day of the week and the gathering of the potatoes that day, hopefully, meant that they were not too wet.

By the second week of October the weather had moderated and the lifting of the potatoes continued. A long and labour intensive process in 1905, the sort of task to which the farm hands' wives would often be expected to assist, working alongside their men-folk in the fields.

By Tuesday, October 10, the potatoes were all gathered and the ground was being harrowed prior to being dunged and ploughed. This is a simple operation to report but one that took five working days, the dung having to be driven out, spread and finally ploughed in without any form of mechanisation beyond a fork and the horse plough.

The potatoes lifted, there is a brief mention about the storage pits being covered but no record of them being filled.

Monday, October 9th. Here the diarist, presumably whilst recording the lifting of the potato crop, has used the available blank blotting paper to draw up a sketch of the potato pits into which his crop will be put. There are three pits planned for that year, located between the garden, the stubble and the road.

Into all three pits at the roadside was to put the Maincrop and Factor potatoes. In the middle was to be Up-to-Date and Lady's Favourite; and along side the stubble was to be the British Queen and Suttons. The year's crop, presumably packed into the pits as the diagram indicated, was covered on Tuesday, October 17.

In these last two weeks of the month the weather had again turned "bad". This incidence of "bad days" recorded, and presumably the intensity of those days led the diarist to record weather for the Sundays, "Very bad day", something he had not done throughout the earlier parts of the diary. Despite the weather the seasonal farm work continues. Ploughing takes its toll on the ploughs and extensive repairs including a new sole, side and fore breasts, have to be effected a Keilhill Smithy. The pulling and driving of turnips is also becoming a constant feature of the diary, an occupation not to be relished on a "very bad day".

The integration of the rural society at the turn of the century is a feature that stands out from the diary entries. The farm was a large centre of employment and in addition supported an even larger number of dependants. Their, and the farm's needs, were serviced from the surrounding community as far as possible, although we have noted the increasing regionalisation of farming which the integrated railway system was able to service.

Bowiebank used coal as the major winter fuel, supplied by Robertson's of Banff. But the farm also made as much use of its own firewood as possible. Similarly with timber, the trees are felled on the farm and the branches used as firewood. The larger timbers are sent to the local carpenters and from them are collected paling posts and carts are repaired.

Corn chests are built from farm timber by the local carpenters in this society, which is not as prone as ours to generate waste material. Even the sawdust made from the manufacture of farm equipment is collected and used as animal bedding.

With a final flourish to this tale of recycling, come the entry from Monday, October 23, "At Gellymill Mill with 5 quarter of Oats for Reith, Carpenter" in payment for the work done.

PART I: BOWIEBANK FARM, 1905: When the Horseman reigned supreme

Banffshire in November, 1905, was a month of mixed weather according to George Wilson. His recordings of "fine days" and "bad days" are interspersed with "very bad days" and "soft days"; and there is even, on Monday, November 6, the entry of "splendid day". Probably the sort of Banffshire day of clear, bright sky; a day of perfect peace with a strong sun filtering through the trees and reflecting back from the River Deveron. A day upon which the diarist would have walked his rounds of the farm, seeing the men and horses busy with the ploughing in the fields above the river. Perhaps that phrasing of men and horses should be re-written as horses and men because the working horse was very much an equal, if not superior to his ploughman in the farming world of the Diary.

The working day of the horseman, supreme amongst the agricultural workers, was built around the work that could be expected from the plough-horse and the rest periods were likewise, the rest required predominantly for the horse and only secondly the man. At the start and end of the horse's working day, the ploughman was still in attendance; feeding and grooming his charges and seeing to their needs.

In the organisational hierarchy of the farm of 1905, first came the owner or tenant. Some 30 years before this would undoubtedly have been the tenant, but the impact of Free Trade and falling world prices of agricultural products had caused a severe agricultural depression in Britain.

This, in turn, had led to manpower reductions on the farm and increased emigration; severe problems and bankruptcy for tenants and with falling rent rolls for their landlords. Many of the great estates of Britain were broken up in the last 30 years of the 19th century and sold off to the tenant farmers, if they had the substance, or could borrow the money to buy them. Very often the estates were not sold to the tenants but to creditors to pay off the debts of the estates which had continued to rise with expenditure well beyond the current or likely future estate revenues.

With the benefit of some historical hindsight, it is now possible to identify the end of the 19th century and to give it a convenient tag, as the period of great general depression. It is important to remember that the people living through those times were not blessed with our hindsight and knowledge of events. They knew that times were hard, had been for 30 years, and were slowly improving. They did not know that the improvements would last. Markets for produce were slack and prices low. Contemporaries knew that the free trade of the world allowed agricultural products to enter Great Britain without surcharges. Average agricultural prices for Britain taken from an index covering the 19th and early 20th century whose average for 1865 and 1885 is 100 shows that average prices had fallen to 72 in 1886 (the average price of agricultural products was .72 of their cost in 1885). Prices had risen slightly to 82 in 1905, the year of the Diary, and had climbed further back to 99 in 1913. The average prices for the period 1855-1875 show the agricultural index price as 120.

A cost of living index for the second half of the 19th century shows that similar falls were registered in living costs; the 1875 index price being 111. This had fallen to 83 in 1895 and was slowly climbing to 92 in 1905 and was at 102 prior to the outbreak of World War I.

Another table of statistics, this time giving the UK average prices for barley and oats, has the following information. The figures as £ per quarter are, for barley in 1905 and 1.22 and oats 0.87.

In 1980, the last year of this table the prices were, the average price of barley was 18.40 and oats 19.10.

Interestingly, the start year for the table, 1771, shows the prices of barley as 1.32 and of oats as 0.86. The price difference of these two grains being little different in 1771 and 1905 and with dramatic price changes restricted to this century, indeed mostly following the ending of the Second World War. The causes and role of spiraling prices in the second half of the 20th century will no doubt become a favourite topic for 21st century historians to debate.

These figures are taken across Britain and include regional variations but do not provide detailed information on them. They are, however, indicative of the general trends that were experienced in Banffshire and, as we have seen in diary entries for preceding months, the onset of the railways had started to seriously erode the regional isolation of markets. The trend was towards the larger national and international markets, with resultant international prices. The break-up of the larger estates, which accompanied these dramatic price falls, was felt keenly in Banffshire with the selling off by the Fife Estates of the majority of the northern lands at the close of the 19th century.

Like many other landholders, the Fife estates were subjected to a marked decline in rent rolls following the downward spiraling of agricultural prices. The decision to stem the outflow taken, all but a small home farm estate surrounding Duff House was disposed of; and what had at one time been one of the largest land-holdings in North-east Scotland was broken up. To be very shortly followed by the sale of Duff House itself, unsustainable and unwanted in the changing economic conditions.

The month's weather was changeable. Two or three good fine days followed by a similar number of bad days and then back again. The first frost was recorded on Saturday, 18th, followed by an even sharper one the following day. The end of the month then settled fine, with only one other frost mentioned, towards the month end.

During this changing weather the ploughmen were engaged at their work, preparing the fields before the worst of the winter weather stopped them.

How different it must have been to have been following the plough on Friday November 3, a "soft day" to following it the next, a very bad day, shirt-sleeves having given way to leggings and waterproofs. Only the frosts and the arrival of the steam mill to thrash the first stacks of oats and barley caused the ploughing to cease.

The steam mill, probably from Robertson's of Banff, arrived on Monday, November 6; part of the previous Saturday being spent in making ready for its arrival. The other work of Bowiebank was held over for the day as all the farm workers were needed at the threshing mill.

The usual numbers necessary to thresh the stacks would be 15; that it

the two men who arrived with the mill and 13 others. Now a farm the size

of Bowiebank could manage to muster this manpower and there is no mention

in the diaries of men being hired in for the day from neighbouring farms

although there are references to Bowiebank men being hired out to smaller

neighbouring farms.

The usual numbers necessary to thresh the stacks would be 15; that it

the two men who arrived with the mill and 13 others. Now a farm the size

of Bowiebank could manage to muster this manpower and there is no mention

in the diaries of men being hired in for the day from neighbouring farms

although there are references to Bowiebank men being hired out to smaller

neighbouring farms.

The Diary, this time, records the stacks threshed that day; being two stacks of corn and three stacks of barley, the outcome being 39 quarters of oats and 31 quarters of barley. The following day they threshed barley, together with another seven half-quarters from the last threshing it was sent to King Edward Station for shipment to Mr Ross of Ballendoch.

The steam mill moved on to the next farm and the work of Bowiebank continued. Added to the ploughing throughout the month came the lifting and driving of turnips; the first to feed and then for storage.

On Friday, November 10, comes the entry, "weighing turnips for competition, Swedish 28 tons 12 cwt., yellow 36 ton some odds per acre". There had been a competition organised by the Turriff Society concerning the weight of turnips grown per acre. The weighing of the yellow turnips was on Thursday, November 16. They weighed in slightly better than George Wilson thought, being recorded as 38 tons 3 cwt.; but whatever the final outcome of the competition was, the Diarist is silent.

The third week of November brought the second hiring fair of the farming year. George Wilson would have gone to Turriff knowing that he needed men to replace those who had determined to leave; their six months being completed. At the hiring fair would be those farm servants, predominantly single men, who had determined to move on to another farm, and there would be the farmers, their would-be employers, for the next term or longer.

That November, George Wilson engaged two new farm servants for Bowiebank. Alex Sheriff as third Horseman at £14 and Frank Ewen, Cattleman at £16. A second horseman would probably have commanded a wage equal to that of the cattleman, whilst the first horseman, as leading hand, would have been paid accordingly. It was usual for the wage to be supplemented by accommodation, coal, firewood and an allowance of meal, and sometimes, potatoes. Indeed, the following Monday one of the hands is dispatched to "Gellymill for meals to servants".

The farm of Bowiebank has its hands for the next six months. The work of ploughing continued as the weather permitted; there being no excuse for getting behind. A delay in ploughing the stubbles could lead to a delay in spring sowing which in turn could lead to a poor crop and difficult harvest. The horsemen and their charges worked through hail, rain and shine, ploughing the land in readiness for the winter frosts.

PART I: BOWIEBANK FARM, 1905: A bleak midwinter

As the seasons turned the month of November and the Feeing Fairs gave way to December and the date for the collection of the Martinmas rents, the farm of Bowiebank was again fully staffed for the winter half year. Farm servants had been engaged at the Porter Fair [Turriff] at the end of November, and those taken on had reason to be considered among the lucky ones, as many men were not engaged. Furthermore, the terms for those who were set on for the winter six months were often reduced from the previous half-year.

An extract from "The Banffshire Journal" of December, 1905:

"Many servants are unemployed at this term. Farmers, doing everything in their power to keep down expenditure in the face of low prices and rising taxes, reduce their staff where possible and to this end they have been helped this year by the harvest season experienced in most districts and the consequent advanced state which other work has reached."

George Wilson's Diary does not provide enough detail to judge whether the farm of Bowiebank was economising on the number of farm servants engaged for the winter half year, but the wages which he records paying - £14 for a third horseman and £16 for a cattleman - were at the better end of the range of wages reported that year. In the case of third horseman, they seem to have been generous. This, coupled with the relatively small turnover in numbers of servants leaving at the term dates, indicates that the farm of Bowiebank and the employment of Robert Wilson, George's father, was well regarded and an engagement to be sought rather than avoided.

The extract from "The Banffshire Journal" of November 28.1905 concerning the Porter Fair states that "There was a large attendance of servants - far exceeding the demand. Business opened stiffly and for some time comparatively few engagements were made, except in the case of boys, for whom there was a fair demand. As was expected, there was a large drop in wages compared with the rates current last half year.

"A good many men very sensibly stayed in their former places, some at a considerable reduction, while others, rather than submit to a reduction, went to open market and engaged at, in many cases, pounds less than they were being offered to stay. Those staying on had to submit to a reduction of 10 shilling and over, while those changing had to take a reduction of 20 shillings to 40 shillings - foremen and experienced cattlemen getting from £14 to £16, the highest known being £17; second horseman £12/10/- to £13 and in exceptional cases £14; third horseman £10 to £12, and boys from £6 to £10. A large number of men left the market unengaged."

It's a short sentence to end the report on the Turriff Porter Fair, but it carries within it the whole range of the distress that was likely to be inflicted on the farm servant who was unable to secure a place. There was little help or sympathy for those men who could not find work and the alternative was to seek work elsewhere. They often migrated south to the cities of Scotland or further afield to England or a passage abroad. Emigration to parts of the Empire was increasingly sought as the depression in agriculture lengthened and employment prospects at home decreased.

The Banffshire Journal of 1905 carried weekly advertisements for several shipping lines engaged in regular sailing's to the Cape, and from there on to the southern outposts of the Empire in Australia and New Zealand. The other favoured destination from North East Scotland during this period was North America, especially Canada. Advertisements in the "Journal" would feature the shipping times and next departures, for which the steerage class passage was about £5. Canada, at this point, was offering free land grants in certain areas. The prospect of leaving unemployment for the promise of a land grant, and the chance to become a self-reliant, appealed to increasing numbers.

For those who could not find the fare, there were other options. At various times assistance with passage was made available to potential emigrants. Another strategy employed was for the fare to be paid by relatives or friends already in the "new world." Shipping companies opened offices and agencies in areas where there were concentrations of people who had originated in a given area and enabled them to purchase tickets that were then transferred to the potential emigrants.

As winter set in and hailstorms swept the Banffshire landscape, those who had no place were faced with a bitter prospect and had hard decisions to make. For those who had been taken on at North East farms there was the prospect of the cold winter work ahead, but security at least of the forthcoming six months.

The staff at Bowiebank complete, the winter work continued, the weather for the first week of December being "fine" with some "frosty" mornings. The weather allowed the season's work to progress and ploughing at Bowiebank was well under way.

The other seasonal work was the pulling and driving of the turnips taken into the farm for feeding and storage against the worse weather to come. The turnips are being pulled and driven daily during the first week of the month, probably by the "orraman". As well as being wanted for storage, they are being fed to the sheep and taken to the cattle sheds. By the end of the first week they had driven enough to spend the day storing them.

The other daily job of the farm during that first week of December was the threshing of oats, usually two and a half quarters daily; by the middle of the week there were enough oats threshed to bruise for feeding.

On Tuesday, December 5, George Wilson was "At Turriff Central Mart with 4 beasts, average £21/12/6." The timing of the delivery of these beasts for sale was significant. They were to become part of the outpouring stock from the North East to London in time for the Christmas market. Beef was still the principal choice of many for the Christmas table, but the increasing numbers of fowl, of every variety, was slowly eating into this lucrative market. "The Banffshire Journal" reported on December 19 that "Senders of stock to the London market have come out of it fairly well, and northern butchers had a large stake of the dead meat market". But they then sounded a note of caution: "A notable feature is the extent to which poultry are ousting meat for the Christmas dinner of the ordinary citizen. Special sales of turkeys, geese and ducks are now held at this season of the year. It is a growing feature of the season that can hardly fail to have an effect on the price of beef".

Another aspect of farm life in this season was the relative shortage of straw available to farmers for bedding and feeding because of the shortness of the crop due to the drought that summer. The 1904 season had also been a poor one for the production of straw, and consequently farmers approached this second winter again deficient in straw but with no reserves from the previous year to carry them over.

Some farms had adopted wooden bedding, while others resorted to whins. The daily threshing of corn was ever decreasing those reserves of straw from the stack-yard. However the farm was to cope with this problem, there must have been an unusual amount of seasonal work to be done that year, as another man is engaged during the first week of the month: "Chalmers" is set on at a weekly rate of 10 shillings (50p).

Perhaps this engagement for Chalmers, as for the cattleman and horseman from the Porter Fair, would occasion an order with one of the large shops in Turriff and that advertised for "Term Trade" in household and clothing goods. The main advertisers in this term in 1905 were Henry Gray and Alexander Shand's Central Warehouse in Turriff and W. Beattie at 15 Main Street, Aberchirder.

The ploughing and the driving of turnips continued daily while the weather held, and alongside this was the collection of draff from Banff Distillery for use in feedstuffs. The other increasing component of winter feeding was the provision of cake and manufactured feed, hence the entry on December 7: "At Macduff. Brought home 1 cwt. oilcake, 1/2 cwt. molaseuil, 2 bags bran from Lime Co. and 10 cwt. Biby Nuts from Hutcheon." Further weekly trips are made to the Banff Distillery for draff, and one more trip to the Macduff Lime Company for 12 cwt. of feeding cake and two bags of bran are made in December.

As well as threshing their own stacks with the farm mill, there was a need for the steam mill from Robertson's of Banff, and this was ordered again towards the end of the month. An entry for Wednesday December 20, seems to indicate that due account was taken of the season of the year in which this day's threshing was to take place: "2 forties for steam mill of beer". While the term a "forty of beer" is unfamiliar, there is little room for doubt as to the implied intent in that entry.

Thursday, December 21 was taken up with preparing for the steam mill the following day and tidying up the corn yard, as well as ploughing, driving turnips to sheep and "carting leaves from front of house". Friday, December 22 was a fine day and, preparations completed, the workers of Bowiebank and the two mill operators from Robertson were able to thresh 54 quarters of black oats, 20 quarters of white oats and 12 quarters of barley.

On December 23 the black oats were delivered to King Edward Station to be taken to Macduff for the Lime Company.

Monday, December 25 was a fine day, and the work of the farm of Bowiebank continued unbroken. Ploughing continued while the weather held, as did the pulling and driving of turnips. Also working that day were the smithies, as the diarist records the shoeing of a three-year-old horse.

On December 28, 20 sheep were sent to Mr Middleton at the Belmont Mart in Aberdeen, and were sold at the Saturday sale for £41/19/-. This was the first record of sheep being sold out of the immediate area; throughout the earlier months of the year, entries concerning sheep sales had them going to local butchers; it may well be that the farm of Bowiebank was expanding its sheep holding.

The diary of George Wilson for Bowiebank Farm in 1905 has provided a glimpse into the farming world of Banffshire 90 years ago - a very different world from the farming of today. Through his diary we have been able to share something of this past; a past that is long gone and which is now only accessible through the records of the time, which provide only a fragment of the picture.

PART II: SOUTH COLLEONARD FARM, 1913 – 1916: The House

Set in the hillside two miles from Banff, stands the white walls and tower of South Colleonard. Built in the 1860s for industrialist George Wilson Murray, the design was taken from a plan by architect John Gordon of Oakleigh Villa.

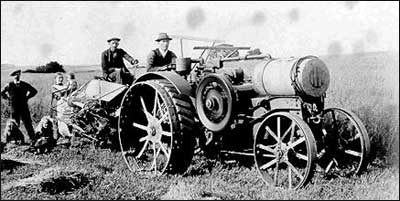

George Wilson Murray had been born in New Pitsligo in 1833, the son of George Murray, one of the first effective granite workers there. He emigrated to Melbourne, Australia, in 1853 where he constructed the Temple Bar in 1862. Murray returned to Banffshire the following year and bought the iron foundry in Banff. Under his guidance the foundry manufactured all kinds of agricultural implements including threshing mills, ploughs, harrows and even steam engines. Pumps were shipped as far afield as Egypt and his reaping machine, "The Victory", was awarded first prize by the Royal Northern Show in 1880.

George Wilson Murray died on June 14th 1887. Five years later the old foundry at Banff was burnt to the ground.

Diarist George Wilson took occupation of South Colleonard in 1913.

PART II: SOUTH COLLEONARD FARM, 1913 – 1916: The Farm

South Colleonard, was at this time, still a part of the estates of the Duke of Fife. The agricultural depression of the last third of the 19th century had caused considerable distress amongst the farming community with crop prices, particularly grain, falling with the influx of cereals from the Americas and the Ukraine. The opening of the vast prairie land of north and south America, coupled with innovations in transportation such as the railway and the introduction of steam passage for the Atlantic, provided the opportunity for a global economy in agricultural produce.

In the southern hemisphere a similar agricultural boom was also taking place, and with the introduction of steam passage, coupled with refrigeration, there was the opportunity for the export of lamb and dairy produce. Britain, the centre of the British Empire, was at the heart of world trade in goods and materials, produce and in services such as banking and insurance; and from a position of strength in the mid 19th century had ushered in a period of unparalleled free trade. However, as the century progressed the new agricultural economies developed, exporting their produce to Britain in ever increasing quantities, there developed a severe depression in agriculture that lasted, with some short periods of relative prosperity, well into the 20th century, before being displaced by more prosperous farming following World War II.

The agricultural depression was to affect all those who were involved in agriculture, from the landowner to the labourer. As prices for grain were forced down, a squeeze was put on the farmer to become more efficient. This was often translated in the short term with a reduction of wages offered at the next term day's hiring fair. Driving down the wages offered to the workers was not a method that would produce any longer term security, either for the farmer of his servants. Many men left the land and emigrated to the new worlds; others left the land and migrated to the towns and cities in search of work in industry. Such removal of men initially helped the farmer to hold down costs and to be more efficient but, as the ebb of men from the land continued, the reverse became true and with the resulting shortage of labour, the farmer had to pay higher wages to keep his servants.

The relationship with the landowner also changed as a result of these price pressures. Rents, set at the 19-year term, became unpayable as prices fell. The landowners were faced with difficult decisions as whether to foreclose and evict tenants for non-payment, with the subsequent re-letting of the farm at what would have to be a reduced rental, or to reduce the rent to the incumbent tenant. Either way, the pressure on rents was downward and as a direct consequence, so was the price of land.

As land prices spiralled downwards landowners had to adjust their expenditure accordingly. Many landowners who took an interest in the running of their estates were able to take measures to reduce expenditure or to sell land and transfer the capital to other more profitable investments but many paid little or no attention to the active running of their estates and did not cut back on expenditure. Other estates were saddled with mortgages that were only sustainable against a high price of land and, as prices fell, were sold; thus driving down the price of land still further.

Against this background of agricultural depression, George Wilson had learned his skills as a successful farmer at the knee of his father and in 1913 at the Indian summer of the British Empire he set out to farm successfully at South Colleonard.

The Fife Estates that had once covered the North East were now reduced to a core holding centred on Duff House (although this was disposed of by the estate as being a financial burden). The estate had, rightly, foreseen the downward spiraling of land prices and had got out of agriculture and invested in the City in the late 19th century but had retained a presence around the redundant house for social purposes. One of the manifestations of social acceptance in Britain was, and possibly still is, the holding of landed estates and the pursuit of traditional country pastimes.

George Wilson removed to South Colleonard on May 28, 1913, that being the spring term day. The removal of a whole farm at the end of the 19-year lease was an operation that required careful handling. Horses and carts, as well as livestock, took longer to move than nowadays. If the journey involved coming over the Banff Bridge, as would now be the case, then there would have been another obstacle at the Banff side of the bridge that is today not apparent; namely the gates and gate lodges of Duff House itself. The gates were locked and traffic progressed down towards the Old Market Place and then either up Bridge Street or Carmelite Street to leave the town.

Perhaps George Wilson had managed to either obtain permission, as an incoming farmer, to use the estate road or had been able to temporarily ford to the Deveron, thus reducing the journey distance and time. The diaries tell us little of the move other than it took place presumably without any major incident.

Preparations for the move would have been under way for a considerable time. George would have been making the detailed arrangements with his father for the latter's retirement and for taking over from him such men and equipment as he felt he needed for his new farm.

George would have offered new positions to the men at Bowiebank whose services he wanted to retain for South Colleonard and probably have had the pick of horses and carts, as well as the other machinery he would need. Detailed financial discussions would then have been carried on between father and son as to the value of the selected items, and settled. The residue of the farm goods of Bowiebank, other than those retained by the incoming tenant, would have been rouped [auctioned]. As incoming tenant, George would also have had to make arrangements with the outgoing tenant to take over the planted fields of grain and also the straw that remained at South Colleonard. Such a process of valuation would, of course, be fraught with the probability of disagreement and stalemates that could have reduced the countryside to a standstill every term date. To prevent this from occurring the Fiars Courts still sat at this time.

Fiars Courts were a medieval institution that had been put in place to set area and latterly regional prices for a standard range of consumables on an annual basis. Composed of the leading persons of the area, the table of prices, when set (for foodstuffs and basic goods) was then used as a method for determining the wage rates that were needed to offset the prices fixed. The use of the court for setting wage rates had long since fallen into disuse but they still met annually to set the rates for farm produce that were then used as the basis for the agreements at term day.

George Wilson made the agreement with the outgoing tenant of the farm on the value of the sown crops and of the straw. At the end of April he was able to either have the outgoing tenant, or more probably his own men from Bowiebank, prepare the ground for turnip crops and get ready to clean last year's turnip ground to be sown with grass. He probably had two teams working at South Colleonard from the end of April and during the whole of May to get the fields ready for his first, vital, year.

Against the background of a general agricultural depression, how had Bowiebank been successful? The answer to this lies in the strategy adopted by Robert Wilson for his farm. The most severely affected parts of agriculture were those that competed directly with the more efficient producers overseas, i.e. grains (especially wheat), lamb and cheaper beef and dairy products that could be transported, cheese and butter.

North-east farming and the climate are not suitable for efficient wheat production, and the majority of the barley produced had a ready market in the nearby distilleries. The principal grain was oats and there were not enough significant imports of this to seriously damage prices. Bowiebank, especially when George was grieve, had developed a herd of pedigree Shorthorns from which their stock was continually improved. The subsequent beef production was directed towards the upper end of the market which was less susceptible to exterior pressures. The greater part of the farming that George learned from his father, and the Shorthorns that were his special hobby, were reproduced at South Colleonard.

From the available evidence, and for much of this I am indebted to the diarist's son, Robert Wilson of South Colleonard, it would seem that the farm was of the order of 216 acres at this time. Of this, just over 200 were arable, there being some nine acres of woodland on the hill above the farm. Timber was, of course, valuable to both the landowner and the farmer and consequently the standing timber belonged to the landowner and only the fallen timber to the tenant.

As well as the main house, an Italian styled villa, there were probably three cottar houses available in 1913; the wage books for the period record payments for three men paid monthly, who would have been the principal farm servants.

In addition to these servants, there would have been an orra man, a boy and then the female house servants. It is likely that one of the cottar houses was given over to the cattleman, who at South Colleonard was also responsible for the new dairy farming venture.