The Sea

Fisher Folk by Greg D. Allen

Fishermen have been casting their lines off the coast of the north east

of Scotland since before Viking longship keels scraped the shingle beaches

and the Danes set foot ashore around about 794 AD. From Buckie, east

along the rocky shoreline of the Moray Firth to the Knuckle bending from

Fraserburgh southwards round the sandy beaches of Rattrayhead to Peterhead

and down the eastern seaboard to the villages of Footdee or Fittie, Stonehaven

and beyond, communities of fisher folk lived and worked for many generations

in isolation of a larger world yet bound together in commonality of a

hazardous, unpredictable occupation. Their lives were, and are still

today, inextricably bound in a unique history of traditions and beliefs.

Fishermen have been casting their lines off the coast of the north east

of Scotland since before Viking longship keels scraped the shingle beaches

and the Danes set foot ashore around about 794 AD. From Buckie, east

along the rocky shoreline of the Moray Firth to the Knuckle bending from

Fraserburgh southwards round the sandy beaches of Rattrayhead to Peterhead

and down the eastern seaboard to the villages of Footdee or Fittie, Stonehaven

and beyond, communities of fisher folk lived and worked for many generations

in isolation of a larger world yet bound together in commonality of a

hazardous, unpredictable occupation. Their lives were, and are still

today, inextricably bound in a unique history of traditions and beliefs.

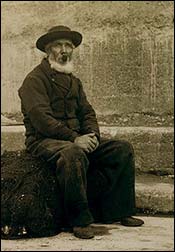

Clay pipe and herring nets. A fisherman at Peterhead, late 1800s.

"Teenames"

In North East fishing villages there were few surnames in proportion to the population. To remedy this and distinguish between the scores of Buchans, Duthies, Ritchies, Strachans, Whytes, Watts etc., living near each other, nearly everyone had a Teename or nickname by which he was usually known. For instance, a man might be called John Stephen “Pettie,” his son would be Pettie’s Sandy, and his grandson Pettie’s Sandy’s John. Another was John Strachan “Jockel,” his son Jockel’s John, and his grandson, Jockel’s John’s Archie. There were some peculiar teenames, such as Jimpit, Jockie Bugle, Orra Borra and Jamie Tobacco. John Duthie “Jeckie” had a son called John Duthie Jeckie’s Jock, and a grandson, John Duthie Jeckie’s Jock’s Johnnie, another was Jock Cow’s Doh!

Very few new villages were built after the late 19th century and the established

communities continued to grow steadily. Those men born in the parish seldom

left to reside elsewhere. The only incomers to the villages would be if

a man took a bride and nearly always she would be a daughter of another

fisherman. There was little integration between country and coast. "Cod

and corn dinna gaun the gither" was a saying of the time. Latterly

it was common for girls to turn to another occupation but sons usually

followed fathers into the fishing.

Very few new villages were built after the late 19th century and the established

communities continued to grow steadily. Those men born in the parish seldom

left to reside elsewhere. The only incomers to the villages would be if

a man took a bride and nearly always she would be a daughter of another

fisherman. There was little integration between country and coast. "Cod

and corn dinna gaun the gither" was a saying of the time. Latterly

it was common for girls to turn to another occupation but sons usually

followed fathers into the fishing.

Baiting lines was a job for the whole family through the 19th and early

20th centuries

(Illustration from "A Stranger on the Bars" DS)

The Women of the Fishing Villages

The pillar of the fishing communities

were the women, stalwarts behind their men and at the fore in all matters

domestic and business, from gathering the bait, baiting the lines and

selling the fish to accountancy and child rearing. An old east coast

saying is no exaggeration; "No man can

be a fisher and lack a wife".

The pillar of the fishing communities

were the women, stalwarts behind their men and at the fore in all matters

domestic and business, from gathering the bait, baiting the lines and

selling the fish to accountancy and child rearing. An old east coast

saying is no exaggeration; "No man can

be a fisher and lack a wife".

Women of the villages, sometimes family but also widows with little income whose husbands had been drowned at sea, known as fish wives, laden usually with the smallest of the catch in wicker creels hoisted onto their backs and held with a rope sling, walked many miles in one day to barter with farmers and crofters for butter, eggs and vegetables. As one Whitehills fisher described; "Cargo baith wyes!".

Often it was the men who replaced the creels on the women’s backs. In Whitehills near Banff the women waded out to the boats anchored in a sheltered cove - the Hythe - with their men on their backs! This was not exploitation but a necessary act, for the men had to spend hours, or sometimes at the Great Line, days at sea and exposure to the elements in wet clothes heightened the risk of illness and with it absence from the fishing and no income.

The Houses

Properly constructed houses began to be built after the Napoleonic

wars in 1815 but conditions could hardly be described as salubrious. A

single open room with an earthen floor regularly sanded below roof beams

blackened by peat smoke. The beams provided storage space for the fishing

gear as well as being used to suspend drying fish, bunches of onions and

rush-pith for wicks for the "eeley dolly" lamp. An iron crook

held the cooking pots over the fire which burned wholly on peats cut locally.

A wooden dresser stored the utensils and a large box bed in which the

family slept were largely the only two items of furniture. Fresh air

in a fisher’s house of the 19th century was in contradiction to

the damp fog from wet clothes in winter and the combination of peat and

mussel bait smells which were an everyday part of their lives.

Broadsea Village, mid 1800s,

by Duthie