The Sea

The Peterhead Whalers, 1788 - 1893 by Gavin Sutherland.

Further reading - The Whaling Years, Peterhead 1788 - 1893, Gavin Sutherland, The Centre For Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen, 1993.

Introduction

The whale oil industry, now considered a barbarous and pointless

pursuit, was once the lifeblood of Peterhead. During the town's hundred-year

whale hunt, when vast fortunes were won and lost, the local population

quadrupled as tradesmen and labourers from the villages of Buchan flocked

to the thriving port for work. Coopers and shipwrights, blacksmiths, butchers

and bakers, all took their share of the town's new-found success.

The growing fleet's demand for deeper water and more harbour space dictated the

harbour improvements that would put Peterhead firmly on the map as an important trading

port.

The whale oil industry, now considered a barbarous and pointless

pursuit, was once the lifeblood of Peterhead. During the town's hundred-year

whale hunt, when vast fortunes were won and lost, the local population

quadrupled as tradesmen and labourers from the villages of Buchan flocked

to the thriving port for work. Coopers and shipwrights, blacksmiths, butchers

and bakers, all took their share of the town's new-found success.

The growing fleet's demand for deeper water and more harbour space dictated the

harbour improvements that would put Peterhead firmly on the map as an important trading

port.

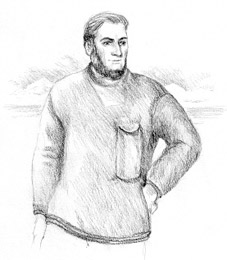

Capt. Alexander Murray of Faichfield, Peterhead, c1885.

A studio pose in caribou-skin arctic gear. Arbuthnot Museum, Peterhead.

"Captains and upper ranks would have worn caribou skins while ordinary seamen would have worn less expensive seal skin clothes". Andrew A. Murray, Blackwood, Australia, 2011.

Political unrest in mainland Europe had all but destroyed foreign competition and with Britain busy Empire-building and the Industrial Revolution well under way, there was still a good demand for whale oil to light the lamps and grease the wheels of progress.

The hunt was a grim and merciless

affair, but times were hard and few of its perpetrators concerned themselves

with the plight of the northern whale and seal herds. Money was there for

the making, and Peterhead's needs

were great.

In 1788, as Peterhead's faithful celebrated the opening of the Broadgate

Town House, the port's first whaling ship left for the Greenland

Sea. At that time the British fleet numbered 255 sail, London being the

leading port with 91 ships, followed by Hull with 36. No one then could

have foreseen the great changes that were to come — by the mid 1850s

England's whaling days were over and Peterhead, with 31 active ships, was

the country’s principal whale-blubber port. The town’s first

ship, the 'Robert', a modest ‘two master’, offered the southern

traders little competition, in fact after ten lean years under English

captains Harrison and then Peacock, her owners were on the verge of closing

down business when two of the principal shareholders, John Hutchison and

James Arbuthnot, made a last-minute bid to save their investment by suggesting

the ship be put in the hands of a local, perhaps more diligent, skipper

and crew. Sandy Geary, a sailor’s son from the old Ronheads, was

promoted to captain on the recommendation of his shipmates and brought

a sudden change of fortune to the ship. On her first trip under Geary the

'Robert' took eight whales and brought home more than seventy tons of oil

(worth £2,000 — a fortune in 1798). Raw whale blubber was processed

into oil by boiling or ‘trying’ and for this purpose the captain

and owners of the 'Robert' bought land on the south side of Keith Inch island

at Peterhead and converted existing buildings into a boilyard — the

North East’s first oil refinery. Soon after the turn of the century

the 'Robert' was replaced by the 'Hope', again under Geary, and the 'Enterprise',

under William Volum, joined her company.

The recently discovered portrait of Captain Alexander Geary (Garioch) Jnr, commander of the Peterhead whaler Dexterity, c1819. (Private Collection).

As the industry prospered the fleet steadily grew, but the northern herds on which they depended, of course did not. By the 1820s over-fishing the Greenland waters forced captains to try their luck in the far-off Davis Strait and Baffin Bay. Whaling had always been a risky business, ice and storms being the whalers’ worst enemies, but the new grounds brought new risks and it was there that many a ship lost its battle against the crushing pack ice. In 1830, the ‘wrecking year’, no fewer than 31 ships from the British fleet of 91 were lost at Davis Strait. Many more returned ‘clean’ (no cargo), each with its own dreadful tale to tell. It was commonplace for ships to become ‘beset’ in the ice floes for days or even weeks on end, but the season of 1830 was the worst ever seen. Returning captains reported cases of severe frost-bite, scurvy, madness and death.

DS - Harp seals were killed in their thousands for their skins and blubber oil

Life at Sea

The social gap between a skipper and crew could not have been wider. Even at the highest polar latitudes, on the rare occasions when work was slack and the weather allowed it, ships’ masters would entertain each other to dinner. At Captain’s table the strictest rules of Victorian etiquette were religiously observed as guests — ships’ officers, surgeons, and sometimes ‘travelling gentlemen observers’ — enjoyed freshly-shot sea fowl, usually eider duck or diver, washed down with a fine claret, and followed by brandy, conversation, and a rubber of whist. Below decks the scene was quite different. A persistent fog of tobacco smoke filled the crowded crew’s quarters where ‘half n’ half’ — a mixture of porter and gin — flowed liberally, and Shetland fiddles played as bawdy songs were bellowed out with passion.

The ‘whale-boys’ were, in the main, a rough and ready bunch, deeply superstitious, and God-fearing to a man. A Sunday never passed without a time of worship, but it was not unknown for a service to be interrupted by the ‘blow’ of a whale. Men would rush to their boats, Bible in hand, and after slaughtering the poor beast return to their psalms and prayer. Harpooners ruled the roost below deck, and not without good reason. They had experience in every field of work at sea and their journey up through the ranks was long and hard. Even more importantly it was their skill and judgement that made the difference between a good pay and a poor one when at the end of the trip shares of the oil and bone profits were handed out with the wages.

Whaling was a seasonal trade. As the winter storms began to subside the fleet left, amid great celebration, for the Orkney or Shetland Islands. There the mainland crewmen were joined by a complement of islanders, men who were known to be expert boatmen and first-class hard weather sailors. With the ships trimmed for a rough passage north, and extra sand ballast and fresh water on board, the fleet then made for the sealing grounds of either east Greenland or the Labrador coast. The timing of the fleet’s arrival was crucial to the trip’s success. The huge herds of harp seals would only be on the ice for a couple of weeks, soon after they had pupped in early April they returned to the open sea. The kill was a brutal business and thousands of pups, favoured by the fashion world for their soft white coats, were clubbed and axed when only a few hours old. With the skins salted and blubber casked, the smaller ships, the sealers, left for home, often with a good number of letters for the wives and sweethearts of the crews who would now be heading for the Greenland Right Whale hunting grounds off Spitzbergen or the Bowhead Whale hunting grounds in the bays and inlets of the Baffin archipelago. The ships were among the whales of the higher latitudes by mid-May. Greenland Right Whale was so called because it was, in commercial terms, the ‘right’ whale to catch. It was a slow docile creature, and it carried a good supply of blubber. It also floated when dead — a most important point. One third of the Right’s body was its head, and this meant a good yield of highly priced whalebone, a tough yet supple material found in the animal’s mouth which acted as a plankton sieve. It sold in later days of trading at little less than £2000 a ton. Though whalebone had many uses, from carriage springs to umbrella spokes, market prices were governed by the major fashion houses’ demand for bone stays.

The Chase

When a whale was sighted by the mast-head watchman he would signal the duty watch below. Two boats, each with four oarsmen, a steersman and a harpooner, were then launched and rowed hard towards the whale. The harpoon, bound to several hundred fathoms of line, was shot into the whale from close quarters, the object being not to kill the beast but to let it swim or dive while fast to the boat until, after several hours, it would lie on the surface exhausted. The whale was then lanced to death and towed back to the ship. By this time the boat crews were often many miles from ship and the journey back could take more than a day. The whale was chained to the side of the ship and its blubber cut away in strips and taken aboard. The last task was to get the head on deck and cut out the whalebone. The scrap or "krang", was cast adrift and the men made ready for another chase.

Iron, Steam and Ice

By the 1860s the modern steam whalers of Dundee were threatening Peterhead’s pole position in the industry and owners in the North East were faced with the choice of fitting their ships for steam or retiring them to the Baltic timber trade. The "Innuit" was the first iron hulled steamer to operate from Peterhead. Two years after her introduction the Peterhead Sentinel announced "The Launch of an Iron Screw Whaler" on the 4th February, 1859. Built in Jarrow, the ship was named "Empress of India" and it was generally thought that heavy iron hulled vessels were the answer to many ice navigation problems. But, as was soon to be proved, iron was not at all suited to the severe northern climate. The "Innuit" and the mighty "Empress of India" - on her maiden voyage - were lost in the Greenland Sea, 1859. Though no lives were lost it was a disaster for the Peterhead fleet. It was later concluded that the extreme temperatures had caused the iron hull plates to contract, so loosening the rivets and causing the inevitable break-up of the ships.

"The Shipwrecked Mariners Society has awarded the following sums to seamen wrecked at Greenland in the "Empress of India" and "Innuit" for loss of clothes, through Mr Robertson, solicitor, Honorary Agent at Peterhead, viz:- George Martin, £2 7s 6d. George Murray, £1 17s 6d. Andrew Catto, £1 10s. Benjamin Buchan, £1 15s. Some of the crew of the latter vessel belonging to other ports, landed here, were forwarded to their homes by Mr Robertson" - Peterhead Sentinel, July 1st, 1859

In the early 1860s when the local sealing and whaling industry was in decline and the number of boats engaged in it was being reduced, cryolite, a lustrous mineral of sodium-aluminium fluoride, sometimes known as Greenland Spar, an early source of aluminium and also used in the manufacture of soap, became a lucrative diversion. In March 1865, readers of the "Sentinal" noted - "We may mention that whalers and doubled vessels are the only bottoms suitable for the cryolite trade as the ships have often to smash through fields of ice before they can arrive at their loading stations. It is fortunate in these days of depression in the whaling interest that another interest has arisen for which our heavy ships are so peculiarly suited".

"Windward", built as a sailing whale ship at the Stephen and

Forbes yard, Peterhead in 1860, was fitted with steam engines along with

the "Mazinthien" in 1865. Many owners could not afford to have

their ships converted and fleet numbers fell quickly. Aware of the success

of John Gray's 'Mazinthien' the captain's brother, David Gray

III, had the famous ship 'Eclipse' built to his own specifications

in Aberdeen, the following year.

"Windward", built as a sailing whale ship at the Stephen and

Forbes yard, Peterhead in 1860, was fitted with steam engines along with

the "Mazinthien" in 1865. Many owners could not afford to have

their ships converted and fleet numbers fell quickly. Aware of the success

of John Gray's 'Mazinthien' the captain's brother, David Gray

III, had the famous ship 'Eclipse' built to his own specifications

in Aberdeen, the following year.

Captain William Penny

1809 - 1892

William Penny was born in Peterhead and like his father before him he grew through the whale ship's ranks to become a whale ship master. In 1850 he commanded a search for the ill-fated ships Terror and Erebus, lost in Arctic waters north of Canada during Franklin's search for the North West Passage.

The new steamer was a fine ship with a devastating catch power. In 1872 a sister ship, the 'Hope', was built for David’s brother John (late of the 'Mazinthien') and it was on that ship that Arthur Conan Doyle made a trip as ship’s surgeon in 1880. Doyle’s ‘great arctic adventure’ later served him well as a source of inspiration for several of his short stories. By now Arctic whale numbers were dangerously low and the little fleet began to hunt lesser game. The Bottlenose whale, the narwhal, the walrus and even the polar bear, animals that in the past had been taken in small numbers, sometimes for sport, were now being hunted in earnest — a sign that the palmy days of the Peterhead blubber trade were over. By the late 1880s it was very much a family affair, the Gray brothers, David, John and Alexander, being the only whalemasters left in the town.

The End of an Era

Realising the futility of the depleted fleet’s efforts Alexander Gray left the whale trade for a new career with the Hudson’s Bay Company. In the summer of ’92 Captain John Gray died at his home in Queen Street, leaving David Gray, by now known as the town’s ‘Prince of Whalers’, the last of a breed of men whose spirited labour had done so much for Peterhead and its folk.

David Gray's Last Trip

After a year ashore, during which time he continued to study his notes on the mammals of the polar seas (by now he was a recognised expert on such matters), David Gray took the town's only whaler, S.S. Windward, to Greenland for the last time. When the ship returned to port on August 7th 1893, Peterhead's most influential industry, and perhaps its greatest adventure, came to an end. Captain David Gray retired to the Links — the house he had built in 1880 which later became the town's cottage hospital — to reflect on his long and colourful career. From his favourite room on the first floor Gray watched with keen interest as work progressed on the breakwaters of the Harbour of Refuge he and his colleagues had done so much to secure for the town. After suffering gout for more than ten years David Gray died at the Links on the evening of May 16th 1896. He was buried at the Constitution Cemetery four days later.

SS 'Eclipse' in the Greenland Sea by William Birnie c1880

Launched from Hall's yard, Aberdeen, on 3rd January 1867 the 'Eclipse' cost almost £12,000, carried eight whale boats and a crew of 55 men. After a famous career at Peterhead the ship was sold to Dundee in 1893 and later on to Norway. Renamed 'Lomonosov', the old ship ended her ocean going days as a research vessel under the Russian flag based in Murmansk.